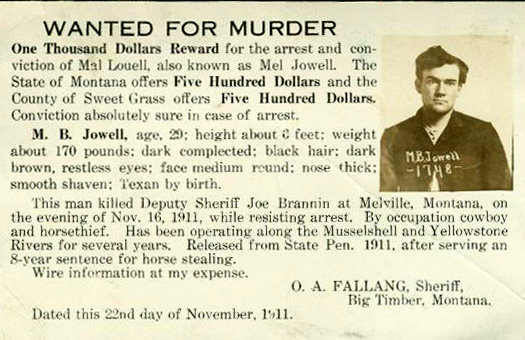

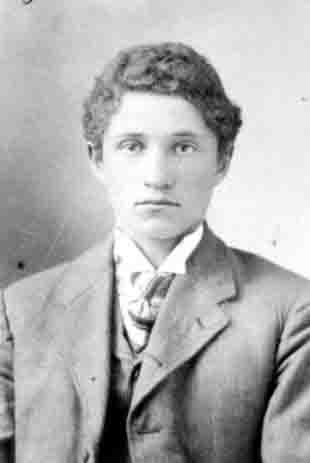

Jowell was a handsome likable fellow. In fact, women swooned when he walked into a room. He was eloquent of speech and pen, able to sway the pendulum his way. One article described him as “uncommonly good looking, and doesn’t look to be a man of hardened criminal tendencies.” In May of 1912, Mel Jowell began serving a 22-year sentence at Montana State Prison in Deer Lodge for the killing of Deputy Sheriff Joseph Brannin on the streets of Melville, Montana in November 1911. He and S. P. McAdams, both serving time, were transported to Livingston, Montana, as witnesses at the trial of Walter Waymire who had been charged with assisting in the murder of Brannin. After the August trial the two men, under guard, were put on the Northern Pacific No. 41 for the return trip to Deer Lodge Prison.

The train pulled up the steep grade at Pipestone Hill near Hell’s Canyon in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest along the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains foothills. Fuel was added to the fire in the belly of the beast as the engine belched steam from the slow-moving train. Two men, joined by chains attached to steel cuffs, slid out of their seats to go to the toilet. Jowell was first to go in with McAdams still attached on the other side of the slightly opened door. He opened the toilet window and somehow managed to get his feet out. In one short movement with a jerk of his hand, the toilet door flung open. McAdams’ coat caught on the door knob but was torn loose as Jowell jerked. McAdams shot out the window behind Jowell. They jumped from the train moving at 30 mph, rolled down the hill and disappeared into the rocky hills. The commotion broke loose so quickly, Sheriff Killorn, only three feet away, was helpless to act. He grabbed and pulled the bell cord, yelling for the trainman to pull the air. The train stopped in short order but before Killorn could alight, the train started moving. By the time it came to a complete stop again, they were a mile away. Jowell and McAdams fled into the rugged wilderness of rough cliffs, rocks and timber.

It was evident the men had assistance in their escape. Jowell had such brash confidence that he would have help along the way, he left a note at the home of Earl Flynn on Trout Creek informing Flynn that “the writer of the note” had been there.

In the note he added, “Tell Fallang that he will have a harder time catching me than he did before.” He openly signed it “M. B. Jowell.” (Fallang was the Sheriff of Sweet Grass County, Montana who pursued him after the killing of Deputy Sheriff Brannin and picked him up in Phoenix, Arizona in December 1911.) One of the men who supposedly assisted their escape was a man by the name of Harvey Whitton.

It wasn’t long after their jump from the train that McAdams was seen at Pipestone Springs freed from his shackels. Jowell was seen at Fish Creek and in Wyoming as he escaped south heading to Texas or Arizona. He took up company with Whitton. The two headed into Nevada, leaving a trail of at least 18 stolen horses along the way, each to replace their spent mounts. Although they had eluded posses and authorities, they were soon pinned down near Elko, Nevada. A shootout ensued. Before Jowell was taken, his stolen horse was shot out from under him. Jowell was dismounted and opened fire on the officers. He failed to hit his target and seeing he was outnumbered, he surrendered. Jowell and Whitton were taken into custody October 14, 1912.

Mel Jowell used the alias of Rex Roberts when he was arrested in Elko. In December 1911, when he was picked up in Phoenix for the murder of Joseph Brannin, he used the name of Dalton I. Sparks. His partner, Harvey Whitton was arrested using the alias of Jim Ross. He was also known by the alias of James B. O’Neal as noted in California records. After serving some time in Nevada, Jowell was returned to Deer Lodge in 1915 under the alias Rex Roberts.

Joseph Shelby Brannin’s life was taken from him November 16, 1911. He left his widowed mother, seven brothers and five sisters to mourn his loss and future generations of nieces and nephews to carry on his legacy.