A Birthday Celebration

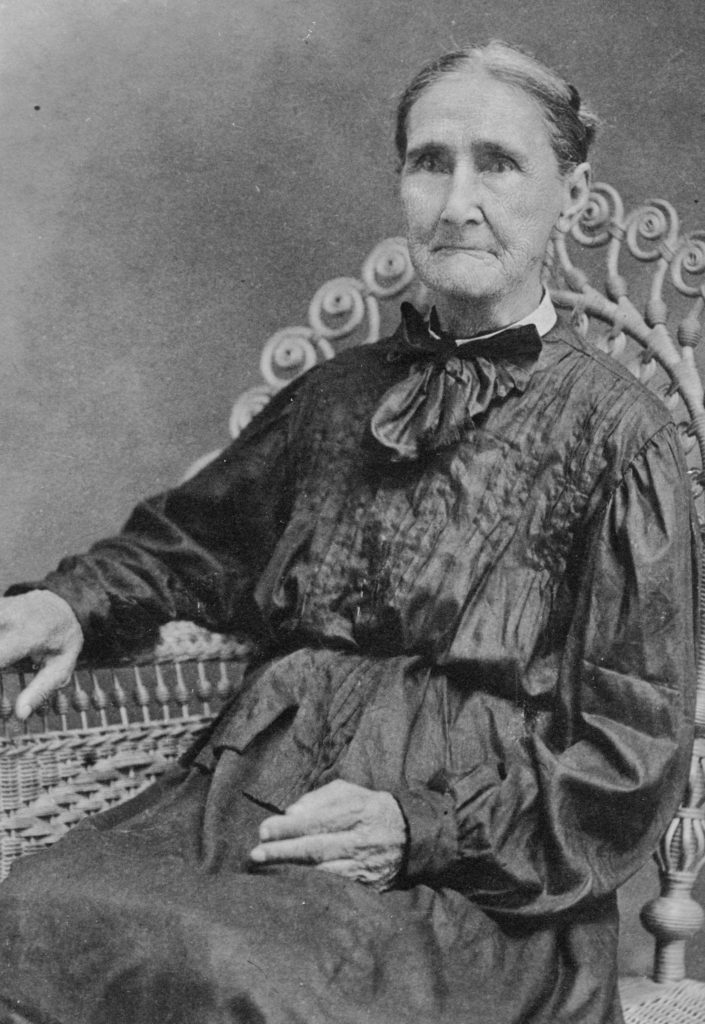

I crawled up in the chair and squeezed in beside the little man. In younger days, I would have plopped down right onto his lap. He looked over at me and gave a weak smile. His chest rose and fell sharply as he fought for every labored breath. He had only been on oxygen for a short time, progressing from a nightly routine to a valuable lifeline. Still, he struggled to breathe. The pneumonia filling his lungs was slowly drowning him. Antibiotics couldn’t even touch the rampant infection that threatened to take control of his body.

It was evident the little man was uncomfortable. He could find no rest whether lying in bed propped up or sitting in the recliner. He had gone with us months earlier to select his recliner. The requirement for the perfect chair wasn’t a matter of comfort. It had to be the right size for one little man and one little girl who brought him a smile and shared his blueberries every morning. That little ray of sunshine was a miracle worker. She brought him life – gave him something to live for.

There was something special going on that day – a birthday celebration. Several family members were already gathered, some came to visit the failing little man, and some came for the birthday party. We all buzzed in and out of the bedroom where he lay in the hospital bed. I took his hand and chatted a minute or just rubbed his little face when I checked on him. Sometimes I just sat by him and held his clammy hand in mine. His words were few. It took too much strength to even try to talk. In fact, it was almost impossible to say anything between gasps for breath. He tried to muster up a smile, his eyes darting back and forth, as oxygen was depleted from his lungs.

Earlier, my daughter had suggested that I had not given him permission to “go on.” Well, I had, but said I would give him permission again. I suggested that she do the same thing. She looked a bit sheepish and made her way to his side and gave her consent. And then, as I sat with him in his chair sharing just a quiet moment, our eyes met. His eyes held a steady gaze. I rubbed his little hand that was in mine and said, “Daddy, it’s okay if you want to go on now.” He gave me a smile and his eyes twinkled a bit. My eyes twinkled a bit, too, but it was because they held tears that began to spill over. I told him, “Daddy, I will miss you.” He whispered, “I will miss you, too.” “I love you, Daddy.” “I love you, too.” That was about all he could muster. Though the words were brief, they forever hold a place in eternity and in my heart.

More times than I can count, the little man had said his goodbyes. For almost twelve years, after my mother’s death, he tried to check out. Every time he was sick, and often when he wasn’t, he said, “I won’t see you in morning.” I would roll my eyes and say, “Sorry, but you will see me in the morning. That just isn’t your choice. When God says it’s time for you to go, then you can go. Until then – same song, same dance.” As time approached for a little girl to turn three years old, the little man promised that he would stick around for her birthday celebration.

That day had come. The tables set up outside, spread with birthday cake, snacks and drinks, were in full view from his bedroom window. Everyone filled his room and we sang “Happy Birthday” to the birthday girl. He managed a slight grin and a slight movement of his hand as if he was mustering the strength to raise it. That was a familiar sight. I had been with him numerous times, as a child and as an adult, to visit parishioners at home or in hospitals. At various times during the visit and before we left, he raised his hand and pronounced a blessing on them. It seemed as we were all gathered around his bed, he was sending himself off with a blessing. Maybe the blessing was for him, but I believe it was intended for all of us as a blessing and a goodbye. It wasn’t long before he seemed agitated. I could tell the crescendo of the chatter bothered him. I suggested everyone leave the room so he could rest. After we left the room, I sneaked back in and just sat with him.

Someone came and delivered a larger oxygen tank and increased the level. I was called out of the room. Reluctantly, I went out the door. I was only gone about two minutes or so. When I returned, there was no sound of labored breath. His chest did not rise and fall gasping for air. His hands were slightly crossed, his glasses laced in his fingers. He was at complete peace. I touched his hand, then his face, and knew that life had left his body. I had wanted to be with him when he left us, but he waited until I stepped out of the room. I needed a deep breath myself before calling the others. It was okay for him to go. He had kept his promise to a little girl.

We celebrated life that day – the life of a little girl and the life of a little man who was endeared by all. Life and death were intertwined in the lives of those two who were the best of buddies. He was invited to another celebration that day. He stepped over the threshold and was met by loved ones and friends. I wonder if they gathered around him along with a choir of angels and sang, “Happy second birthday in heaven” as he raised his hand.

Two years have passed since that day and not a day passes without thoughts of him going through my mind. There are so many things I still want to tell him, so many songs and stories to hear, and so many questions I want to ask.