A Real Life American Tale

If we traced our roots, we would find the vast majority of our ancestors were immigrants. They were drawn to a place called America where they believed they could have a better life, freedom of religion and voice.

Have you ever stopped to consider the challenges they faced coming to “the new world?” Can you imagine the hopes and dreams that compelled them to travel by every mode of transportation available to them? Many did not even make it to America. Some died in sight of her shores, some buried their loved ones at sea. What was waiting for them when they set foot on the shores of a land that promised freedom and opportunity? Who welcomed them with open arms? What if that would have been you instead of your ancestors? How would you feel to be mocked because of your beliefs or because you spoke another language? They came with little of nothing and sought for a place to call home.

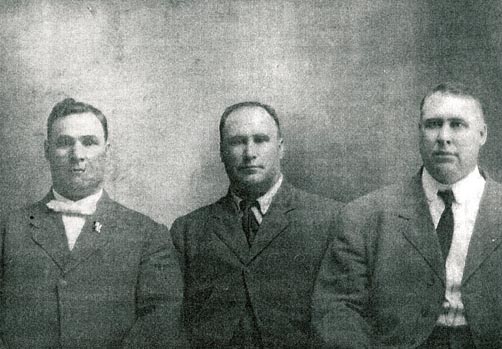

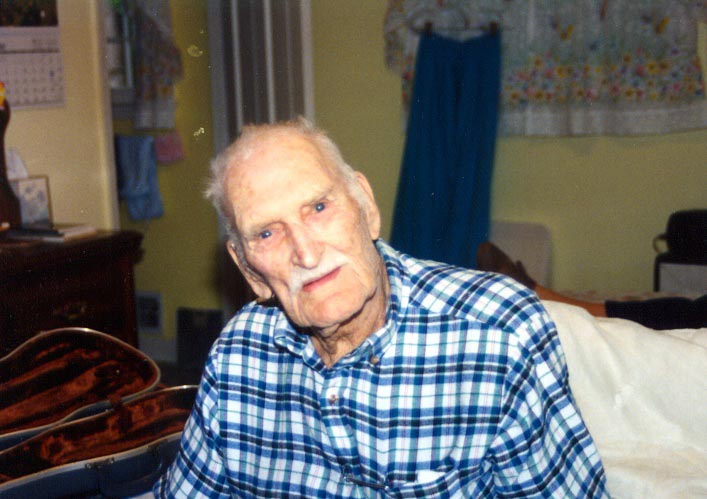

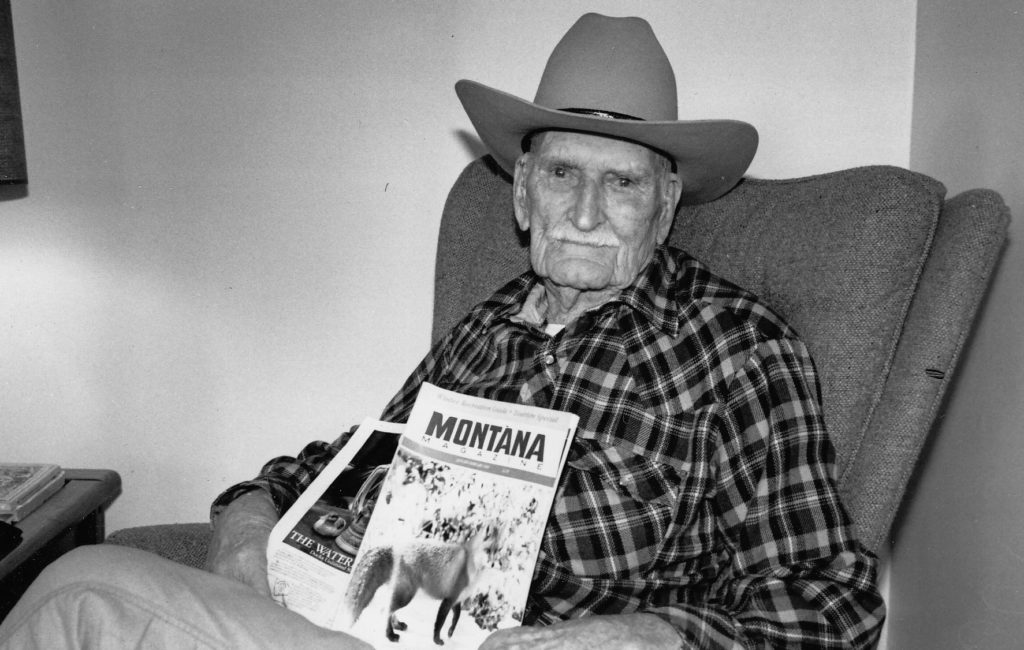

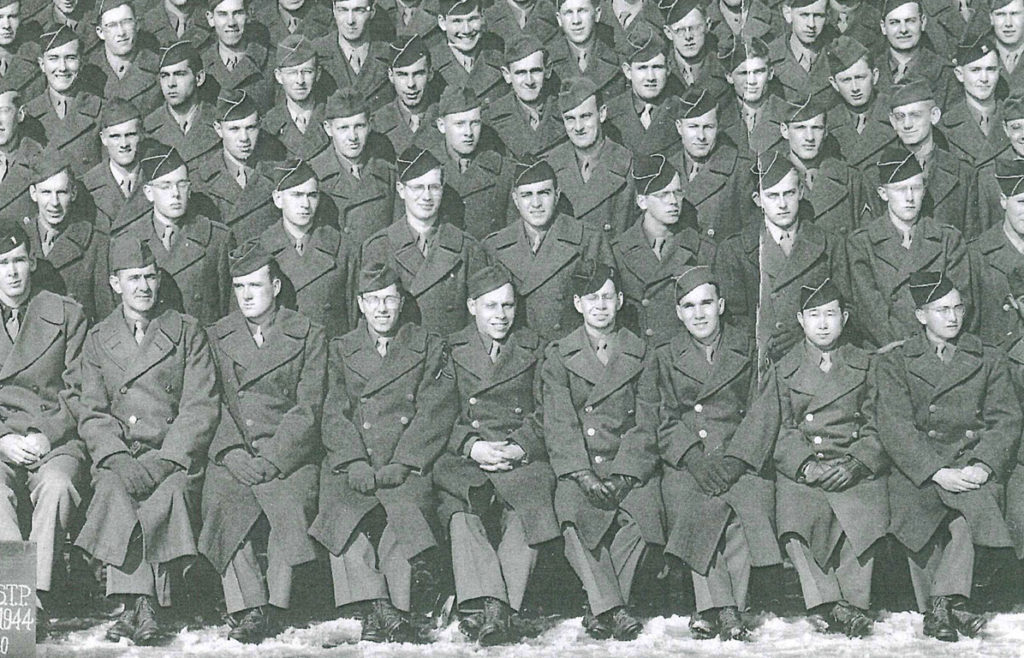

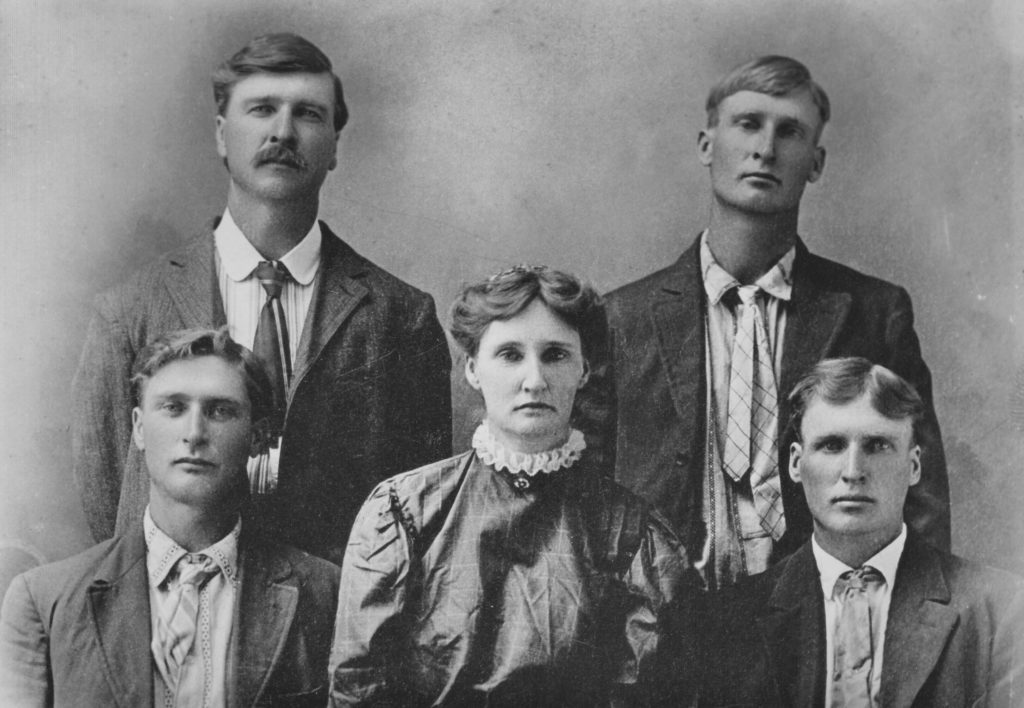

My husband’s 2nd Great Grandparents with their children in 1894. Seven more came later. My husband’s Great Grandfather stands in the middle on the back row.

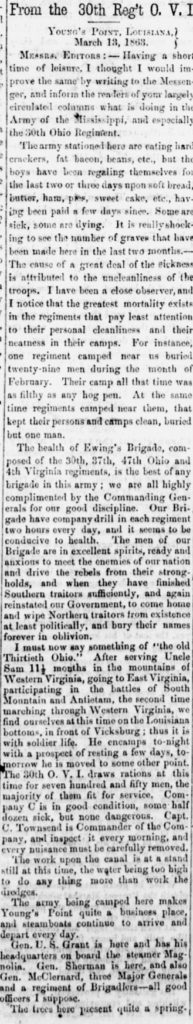

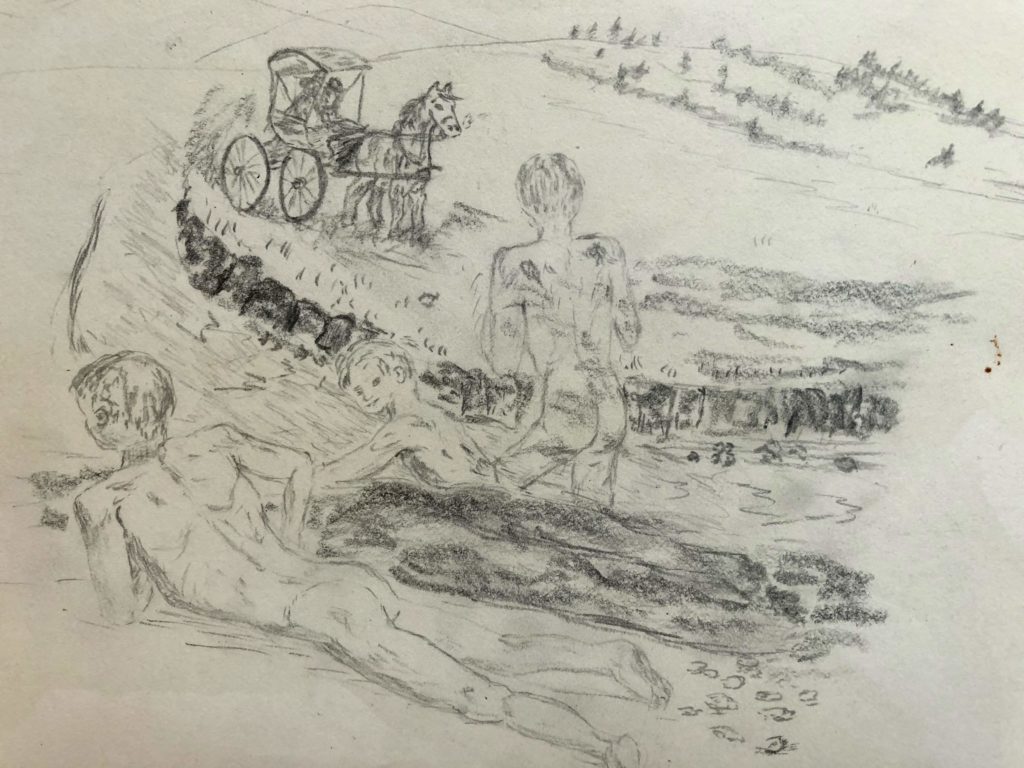

Here is a portion of the account of my husband’s 4thgreat uncle’s account of his emigration from Holland in 1865 that might give us surprising insight as to what it might have been like for our ancestors who made the arduous trip from their homeland.

“In the year of 1856 on the 1stday of May, we left the place of our birth. We departed from Zoutkamp on the 3rdday of May on the water vehicle Toe. After several days we came to Leiden. On the 9th of May we boarded the good ship Arnold Bonniger and the name of the Captain was Anstadt.“

On May 18, they “awoke to see the beautiful high mountains called the Brythergen near Dover (Chalk Cliffs). However, we did not enjoy the scenery for very long, because the swaying and tipping of the ship made some dizzy, others sick, others laughed.”

“Four days later we behold the coast of France and this also was an imposing sight but listening to the conversation of other passengers, I am now beginning to understand how long this voyage is going to take. After some 40 days of sailing we reached a place called New Foundland. It is very foggy nearly all the time and we were anxious for clear weather and if memory serves me correctly, another 14 days elapsed before New York hove into sight. During this time a small, child, belonging to a German woman, died, and it was placed in a wooden box and lowered into the waves. What effect this had on the passengers I will not here elaborate.”

“We were anxious to see the city and this is easily understood as for 48 days our feet never touched earth. A place called Koothe Garden was our next abode, and it was so arranged, the passengers could stay here but there we no sleeping facilities. America which we had so much coveted, but how sorrowful, we stank like strangers in Jerusalem. And what was worse, when we made a purchase, we could not make change, because we could not understand these people…. It was impossible for us to find work.”

“Many times have I been misled to go for employment and could not find one person for instruction, and then later these same people would stand in a circle around me and laugh at the greenhorn. It was driven home to me that the people here are very mischievous and without any kind of organization compared to the Fatherland where everything always was in order.”

On July 4th, the weary travelers met up with their brother who had come to America two years earlier. Upon seeing his condition, they knew they could not stay with him. He was poor in health and the means to feed even himself. At least they were together and that has to count for something.

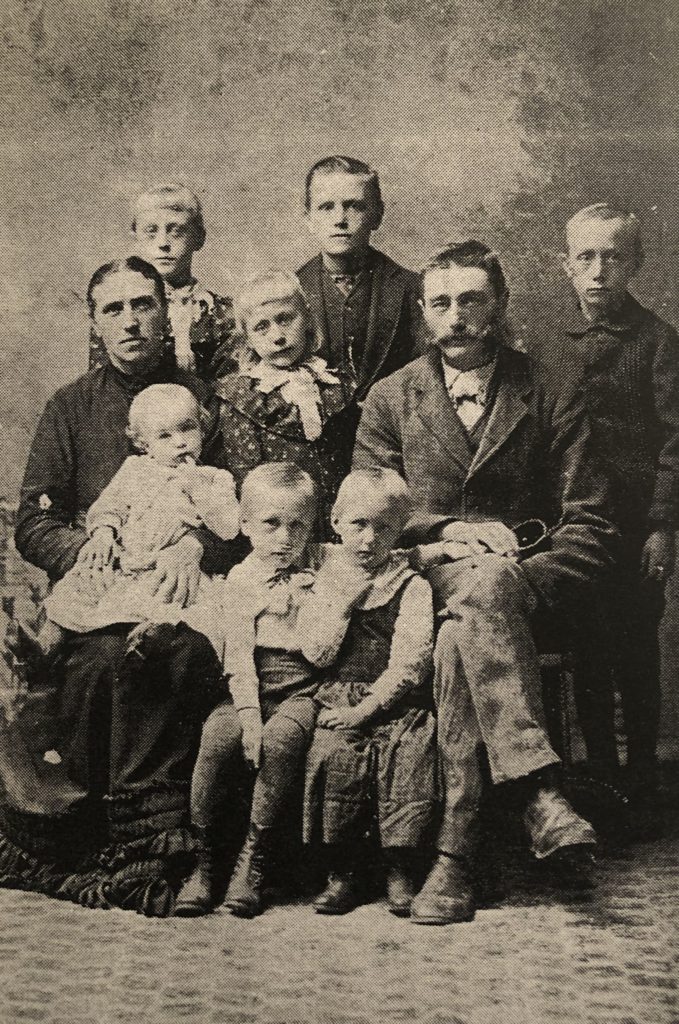

In the spring of 1885, my husband’s Great Great Grandfather, his wife who was pregnant with their second child, and a son boarded the boat to make the trip across the big waters to New York. There, they traveled by train to an established Dutch community in Illinois. Their transition was easier than that of their aunt and uncle. It is said of them, “They never achieved material wealth but were rich in love and religious faith. Basic necessities were never lacking. They earned a living with a sense of pride. Everyone cared for and shared with each other, strengthening the bond that held the family together through the following generations.”

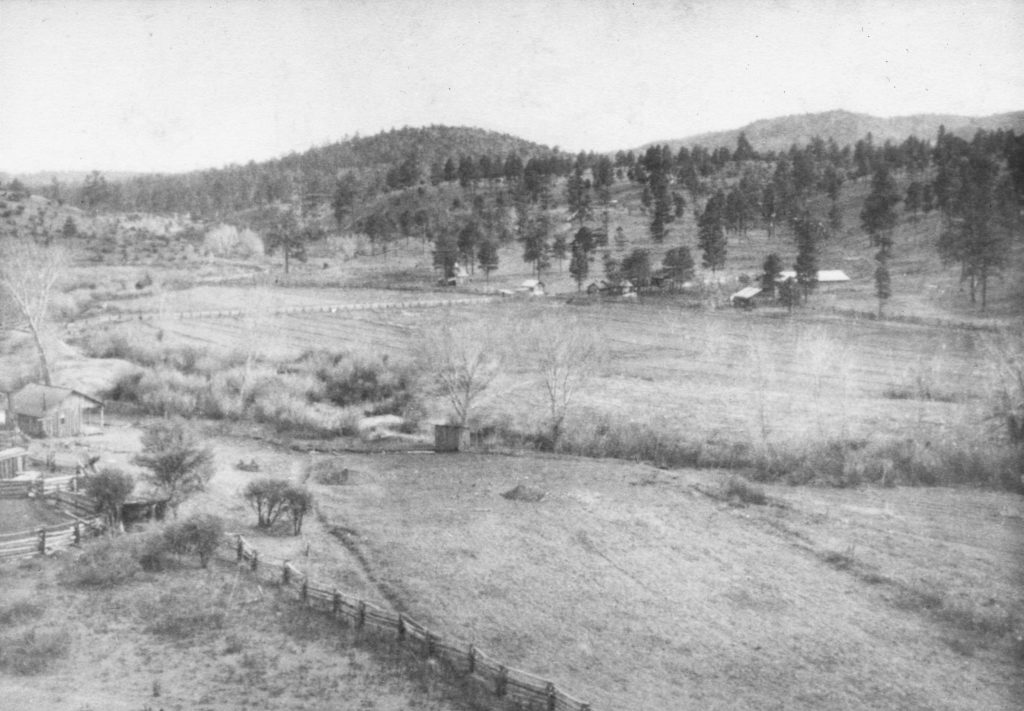

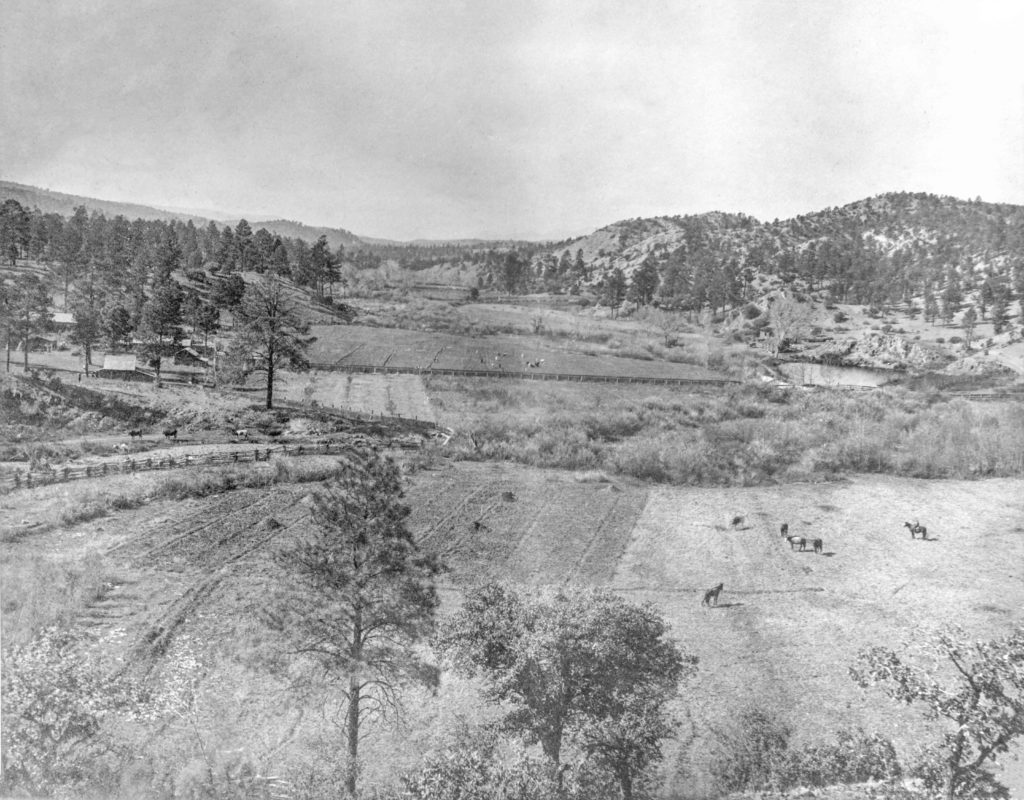

On their farm in Illinois, Great Great Grandparents stand in the middle