If the early settlers in New Mexico Territory thought they would conquer that beautiful, harsh, wild land, they were mistaken. Many were killed or run out of the country by Indians who defended their homes from the invasion of the white men. As Indians were driven from their lands, another wave of settlers made their way into the territory.

The new settlers were a different class of people. They brought in small herds of cattle and started farming or ranching on a small scale until they could increase their herds. With more and more Indians removed to reservations, the settlers no longer had a common foe. The small-time ranchers quickly tired of one another. They displayed their own savagery as they increased their herds at the expense of others, stealing cattle and killing neighbors who got in the way of their enterprise. That time of lawlessness was one of the driving forces for the Brannin family’s move to the tamer wilds of Montana.

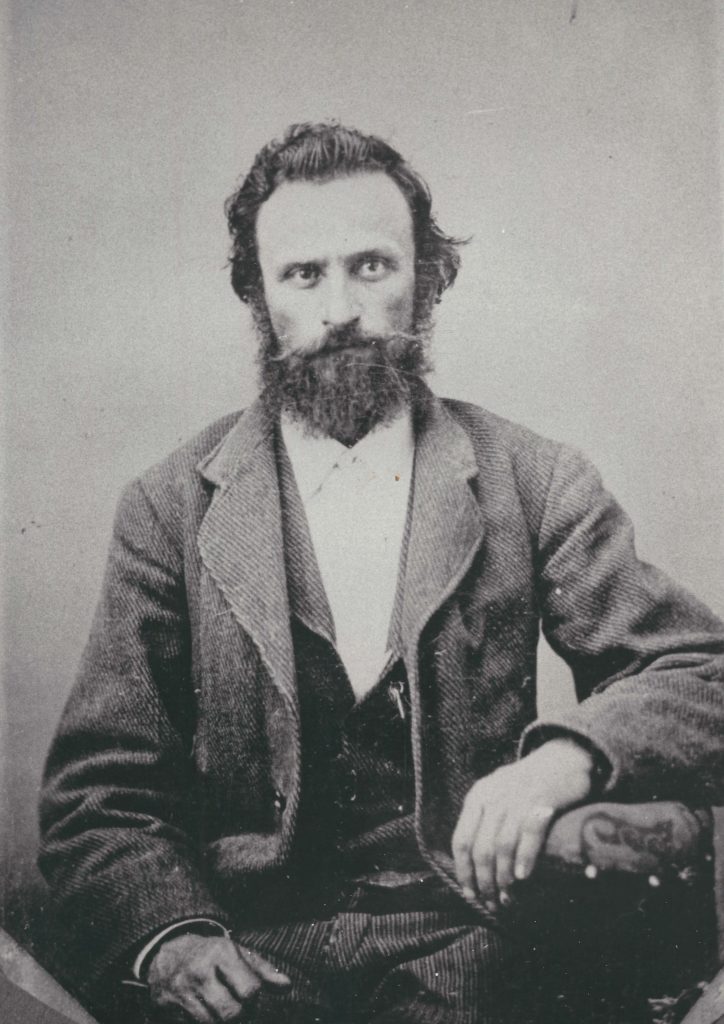

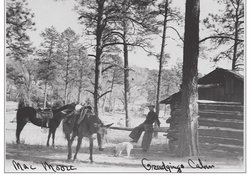

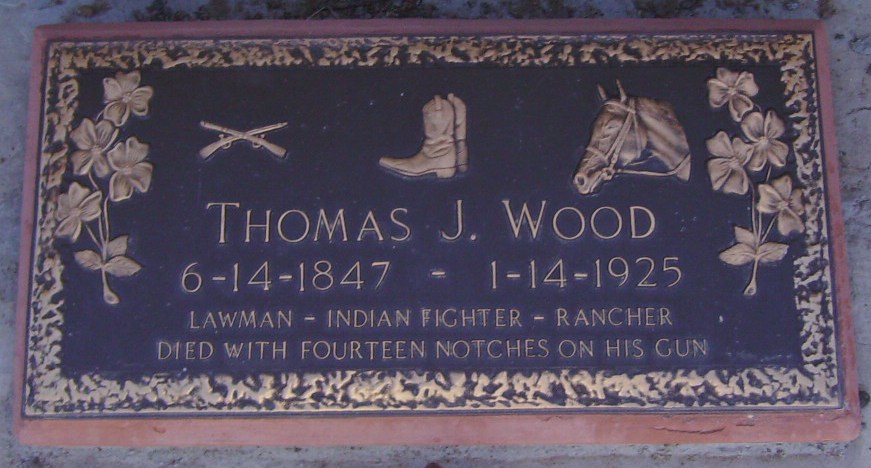

Brothers by the name of Grudgings moved into the area and built a cabin in 1885 near the Gila cliff dwellings. The Grudgings brothers were known cattle rustlers and flashed their weapons with little conscience. Tom Woods, a former peace officer turned prospector, ranched on the Middle Fork of the Gila River northwest of the Grudgings ranch. He was aware of their rustling. The Grudgings boys were afraid he would inform the local ranchers so decided to do away with him.

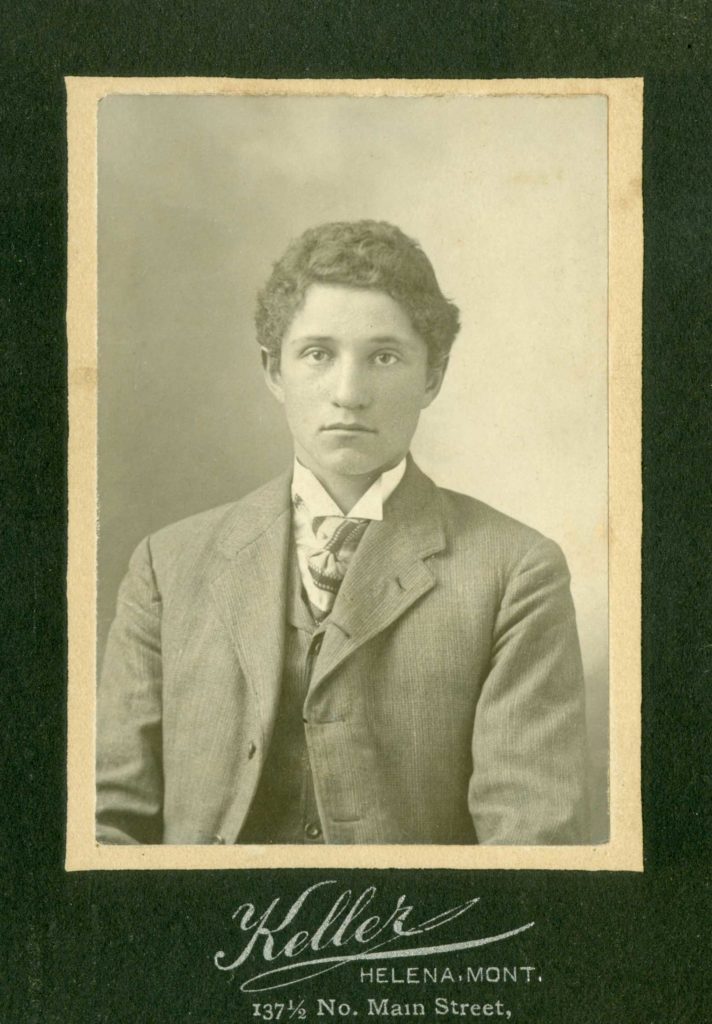

Tom Woods, a pioneer who came west from Iowa, generally made a trip by way of the Gila Hot Springs to Pinos Altos or Silver City to get supplies. On the morning of October 5, 1892, instead of Tom going for supplies, he sent his fifteen-year-old son Charley accompanied by Francisco Diaz, who had been living at the ranch and helping hew logs for a barn. The trail that followed the ridges and curvature of the Black Range was not an easy one. It was not a quick jaunt to town, but rather a journey that took several days. On their return trip from Silver City on October 10, they passed close to the Grudgings cabin in the evening. The Grudgings brothers watched the two pass by with their five burros loaded with supplies and knew the travelers would camp in Grave Canyon just west of the Zig-Zag trail. The brothers followed.

That night, after Charley Woods and Diaz laid down to sleep, they were shot to death. The Grudgings brothers mistakenly thought they killed Tom Woods. Charley suffered gun shots to the head and hands, possibly as the hands tried to shield the barrage of gunfire. There was also indication of blows to the head. The bodies were discovered the morning of October 11.

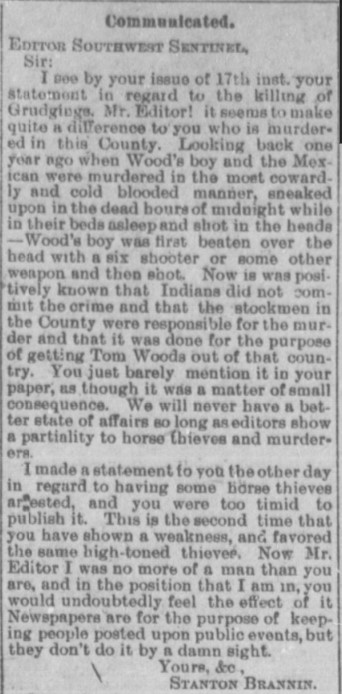

At first, the crime was said to have been the work of Indians or Mexicans. That was quickly dismissed because nothing in the camp was disturbed. All the supplies, the wagon, burros, guns and ammunition were still there, and the camp was completely intact. That meant one thing, it was a deliberate cold-blooded act. Rain in the night “destroyed all signs and trails.” When Tom Woods walked into the camp, he took in the scene, then recovered the single action model Colt .45 he had given to Charley. Tom Woods believed he would find enough evidence to take matters into his own hands. And he did – one year later.

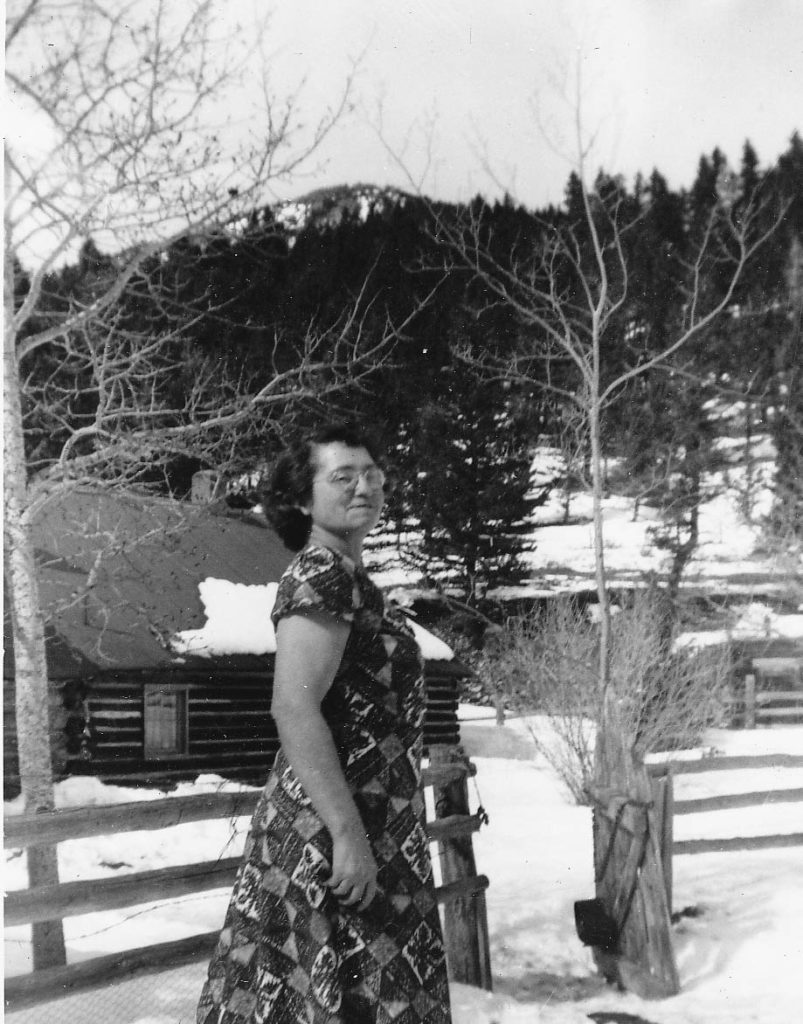

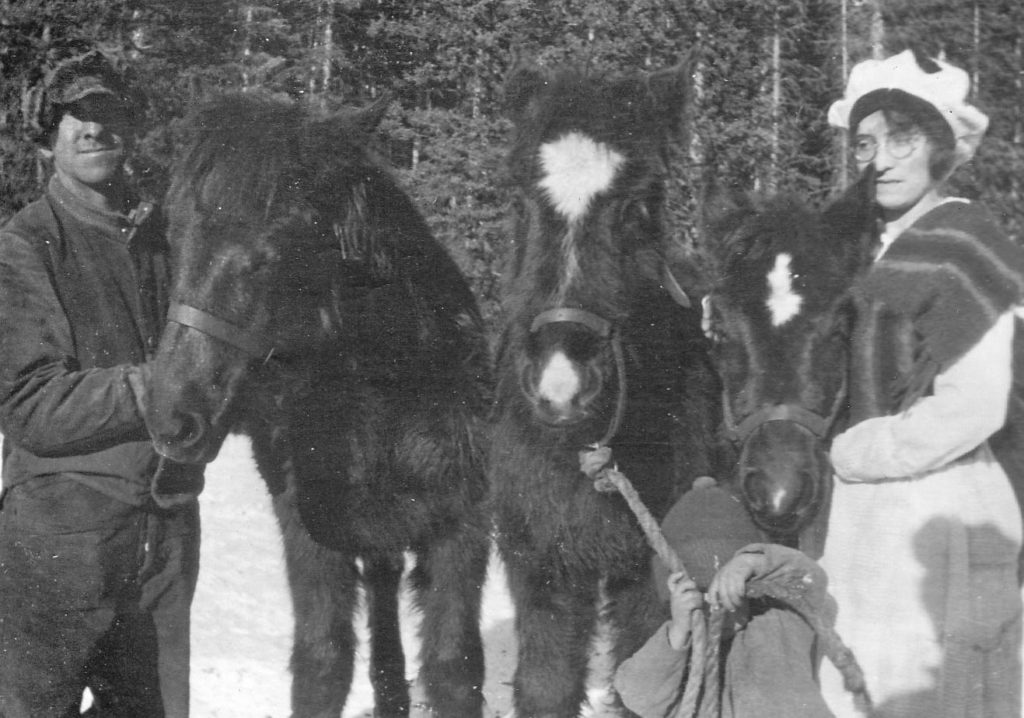

The same night Charley was murdered, he made a “visit” to the Brannin ranch on Sapillo Creek forty miles from Grave Canyon. Charley was a friend and occasional guest at the Brannin ranch. Whenever Charley was there for an overnight visit, he slept in the barn with the Brannin boys. He always slid down the pole that leaned from the loft to the ground. On that particular night, the night of October 10, Dick, age 11, and Gus, age 6, slept in the hayloft in the barn. Normally Joe was with them, but that night he had an earache and stayed in the cabin. In the middle of the night, the boys woke up to see someone in the loft with them who struck a sulphur match on the pole and slid down. It was Charley. The next morning, they wondered about Charley’s visit. Both of the boys swore they saw the “person” and there was the mark from a sulphur match on the pole. It didn’t take long before word spread to Sapillo Creek that their friend Charley had been murdered that same night. As the story of Charley’s ghost has been retold through the years, captivated listeners experience cold chills running down their spines.

That is not the end of the story. A year later, on October 8, 1893, Tom Woods lay in wait for the Grudgings boys in a willow thicket below the Grudgings cabin. The brothers came riding up the trail beside the old rail fence. Woods shot and killed William Grudgings instantly. Tom Grudgings ducked down on the side of his horse and hid behind the rails. Woods shot but missed his moving target.

Tom Woods gave himself up to officers at Cooney and confessed he killed William Grudgings in retaliation of his son’s murder. Though many thought he administered justice, he was found guilty of murder and committed to Socorro County jail without bail. While being escorted to jail, he escaped. The story is that a man by the name of Barrett who accompanied Deputy Fred Golden, went with Woods up the creek for a nature call and was told to “light a shuck,” which Woods did. He wasn’t seen again for some time.

With his Colt on his hip, he trailed Tom Grudgings all the way to Louisiana and determined that a man by that description would cross the river at daylight in a canoe. Woods hid in a canebrake near the canoe early and sure enough, a man appeared. Tom Grudgings had a front tooth out and it was his habit of spitting through the gap. The man spit as he neared the canoe. Woods immediately recognized him and said, “Hello, Tom.” Grudgings swirled around to see the Colt leveled on him. Woods shot him in his belt buckle. Apparently, he was not killed, for records indicate he died in What Cheer, Iowa in 1946 at the age of 75.

After two years of the murder of William Grudgings, Tom Woods was acquitted. The Las Vegas Daily Optic, Las Vegas, New Mexico, dated June 2, 1896, states, “Tom Woods was acquitted of the charge of murder, for the killing of William Grudgings, near Gila Hot Springs, Grant County, four years ago.”

If you happen to find yourself at the old Brannin Ranch site on Sapillo Creek and hear a rustling from a breeze in the old apple tree and smell the faint odor of sulphur, you might just see a faint wisp of a fifteen-year-old boy by the name of Charley Woods.

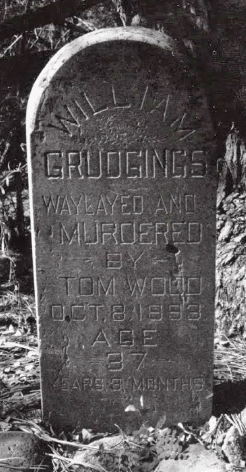

The Grudgings cabin was near present day Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument. The cabin was a tourist attraction for many years until it burned in 1991. Visitors still visit the grave site of William Grudgings whose tomb stone is inscribed, “Waylayed and murdered by Tom Woods Oct. 8 1893”

Before Tom Woods died in 1925 he showed 14 notches on his gun. He said he wanted to get 15 notches on his gun but never got to do that.

According to an article posted in 2014,

https://thewesterner.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-saga-of-wf-co-colt.html,

the Woods pistol is held in safekeeping.