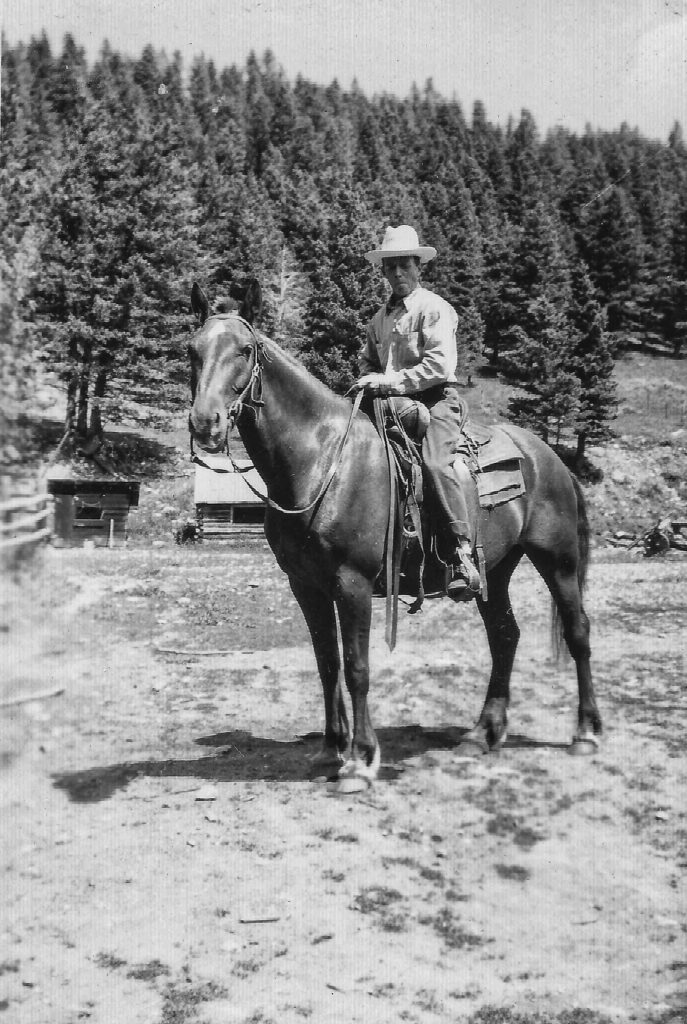

Today my Daddy is my Guest Author again. I had given him the assignment to write about “firsts.” This story is about getting electricity for the first time in the heart of the mountains miles from town.

In the beginning of creation, the LORD GOD said, “Let there be light and there was light.” But not all the time.

On cloudy winter nights (the adults couldn’t see this) an angel gathered up ALL of the left-over patches of light and stored them in a black bucket until the next morning. The mountains were especially dark and spooky. They were filled with creatures that sneaked through the trees at night. Outside there was no emptiness because the darkness filled up everything. It opened enough to let you walk through it like the Children of Israel walking through the Red Sea.

Indoors, it could be nearly as bad. When we were adding a parlor and a bedroom for Mama and Daddy, the new addition encircled an area of darkness which brought a haunt into our house. That was in the daytime. At night THERE WERE TWO HAUNTS.

Sister Ellen braved the darkness to run back into the new addition. She screamed in fright and came back crying. Poor Sister. She didn’t learn things right away. The next night she would try her excursion again!

The big room that served as kitchen, dining room, and sitting room was lighted by a gas burning Coleman lamp which had flimsy mantles that moths liked to battle. The lamp hung from the ceiling. In other parts of the house we used candles or kerosene lamps that had wicks and smoky chimneys which had to be washed regularly. Luckily for children, at nighttime, we had a candle-lighted indoor toilet which was a bucket we pulled out from under the bed.

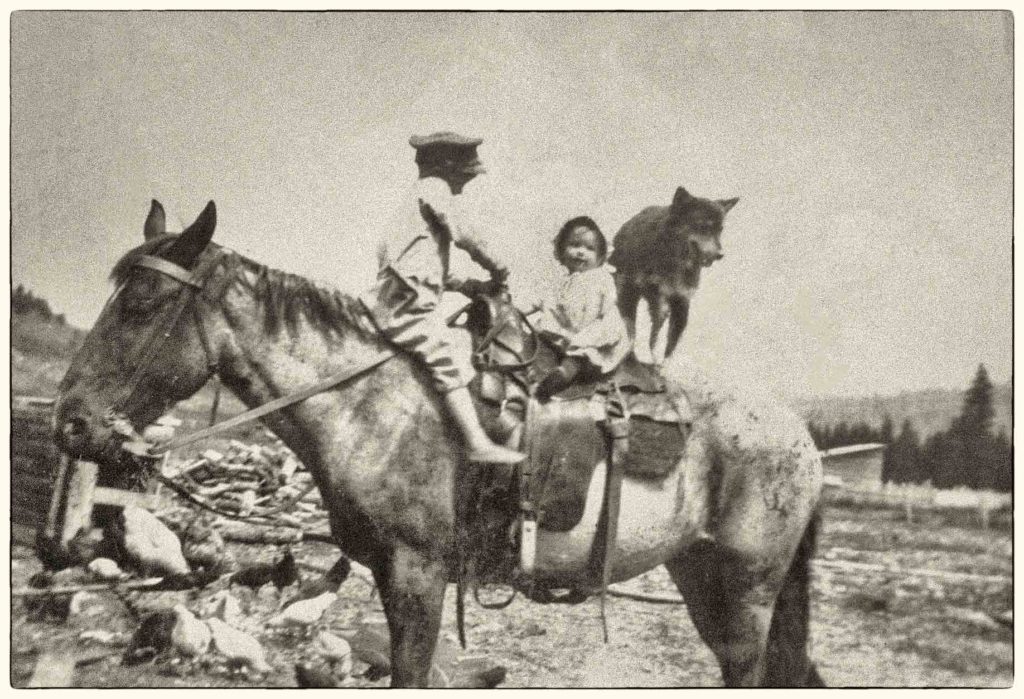

AND THEN! Along about 1929 the uncles built a new lodge and furnished it with electric lights! Their lights only worked when the gas-powered power plant was started and running. However, advances were coming to the Crazy Mountains! Thanks to motivation from the uncles and thanks to Thomas Edison and several decades of development. Our family, living in a log house in the mountains forty miles from a paved road, experienced a first: ELECTRIC LIGHTS! LIGHTS ALL OVER THE HOUSE. And in the shop. At the sawmill. And on both sides of the barn – one set of lights for the milk cows and one for the horses. Before that, in the dark of winter nights, chores were done, and the cows were milked by the light of a hand carried gas lantern.

Our electric lights came by way of a Delco Remy charger and sixteen glass storage batteries. We didn’t even have to start the Delco generator to get our lights.

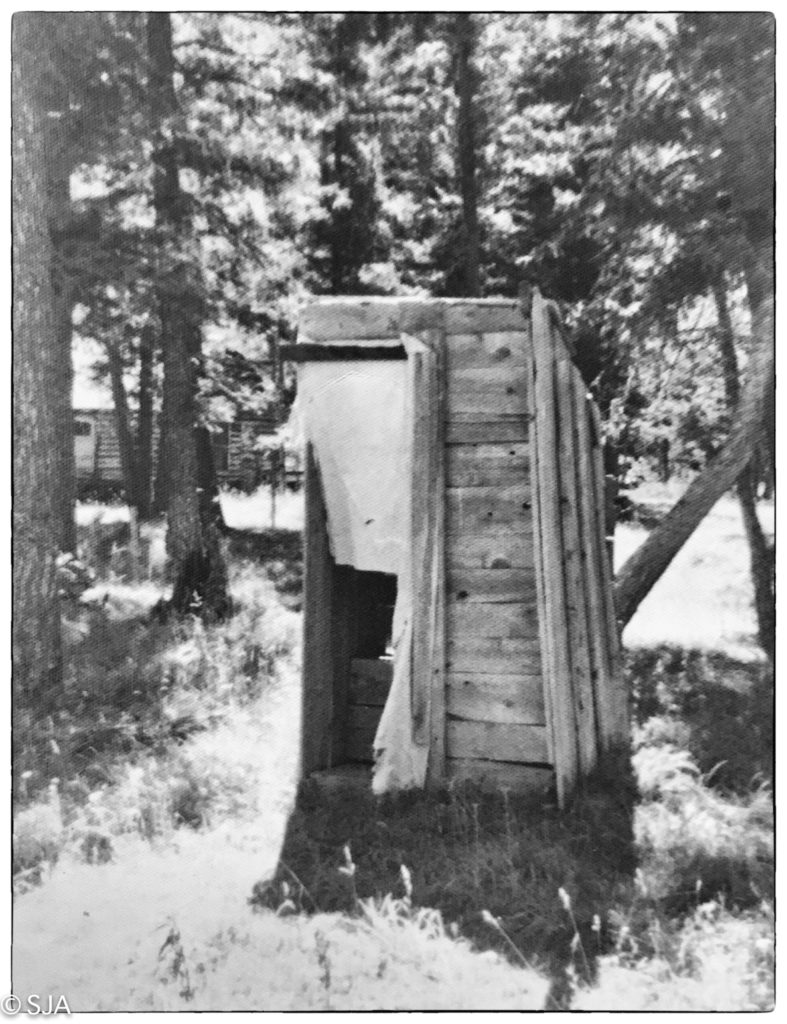

The uncles had electricity and running water in their house. We had electric lights in all our immediate buildings except one. Loretta and Victor had a building like that. She kept a note on its wall:

This little shack is all I’ve got,

I try to keep it neat.

So please be kind with your behind,

And don’t shoot on the seat.

Ours had a Sears Catalogue and no poetry on the wall. But we had a back-up. In the cold of a winter night we had an enameled bucket under the bed.

Outhouse 1975

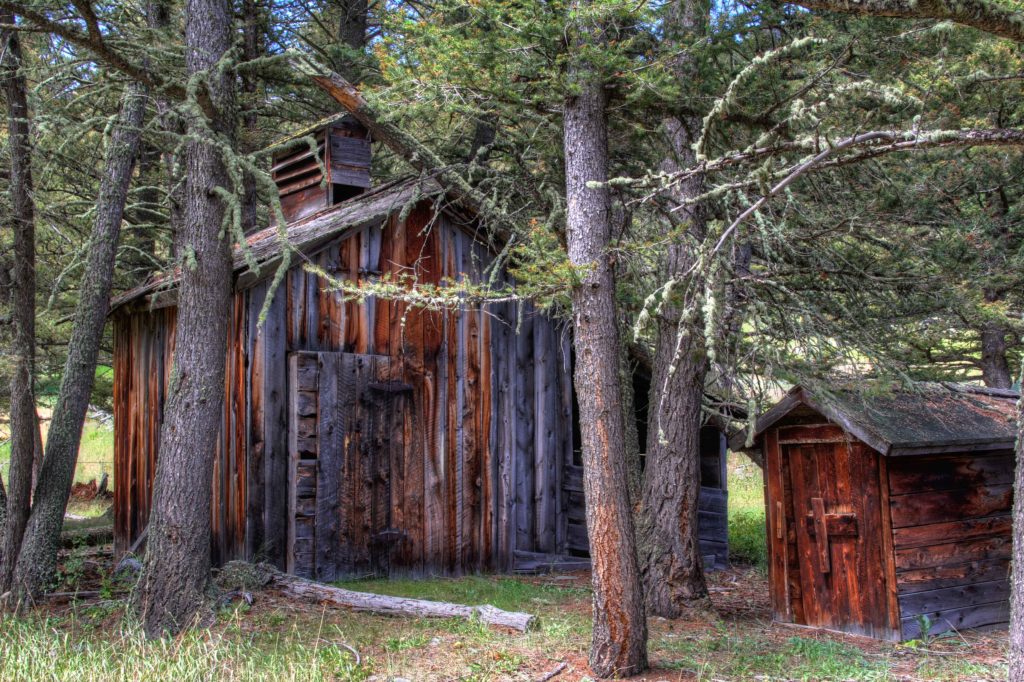

Outhouse 1996

The Delco generator house is on the right

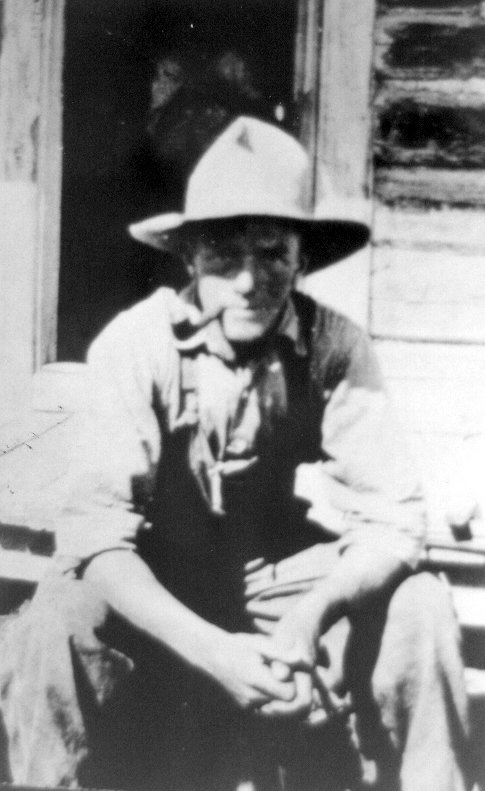

Thanks to the beginning of rural electrification, a secondhand power plant had been advertised in the MONTANA FARMER MAGAZINE. Victor Allman hauled it down from Whitehall, Montana – quite a ways across the state. Lowell Galbreath was working for us, and he knew all about wiring houses, cow barns and sawmills. He soldered eight-gauge electric lines with silver solder. And on a magic day – we had lights controlled by pull strings that were too high for a child to reach. The gasoline powered Coleman lamp was put away and the moths went back to sulking in the clothes closet.