The road to the old home place was not much more than a beaten path riddled with rocks and potholes that led into the mountains, and we managed to find every one of them. We jiggled back and forth when we forded the creek, the sound of stones crunching under the tires.

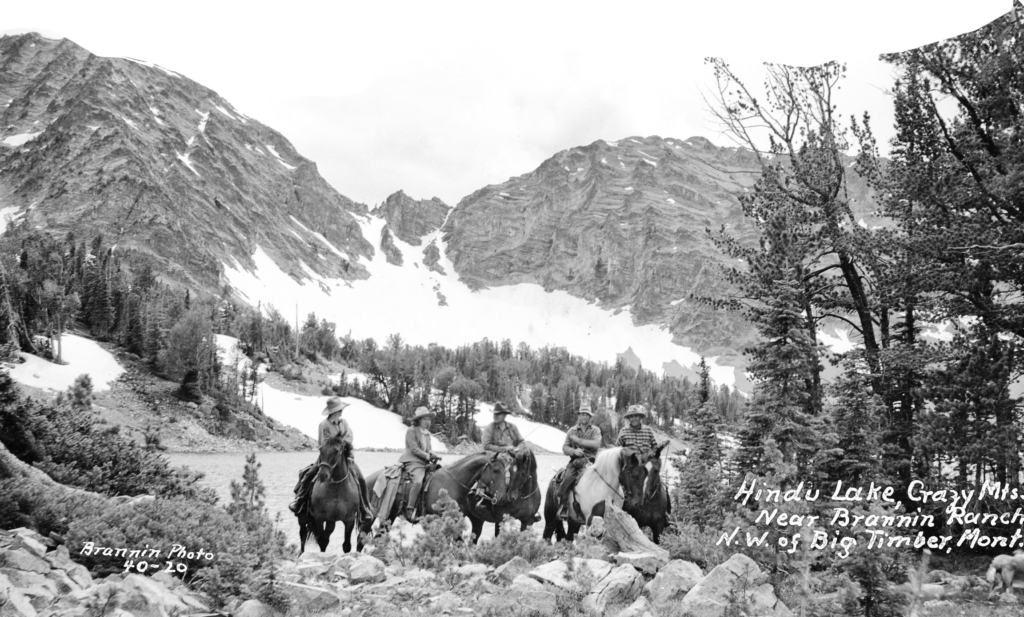

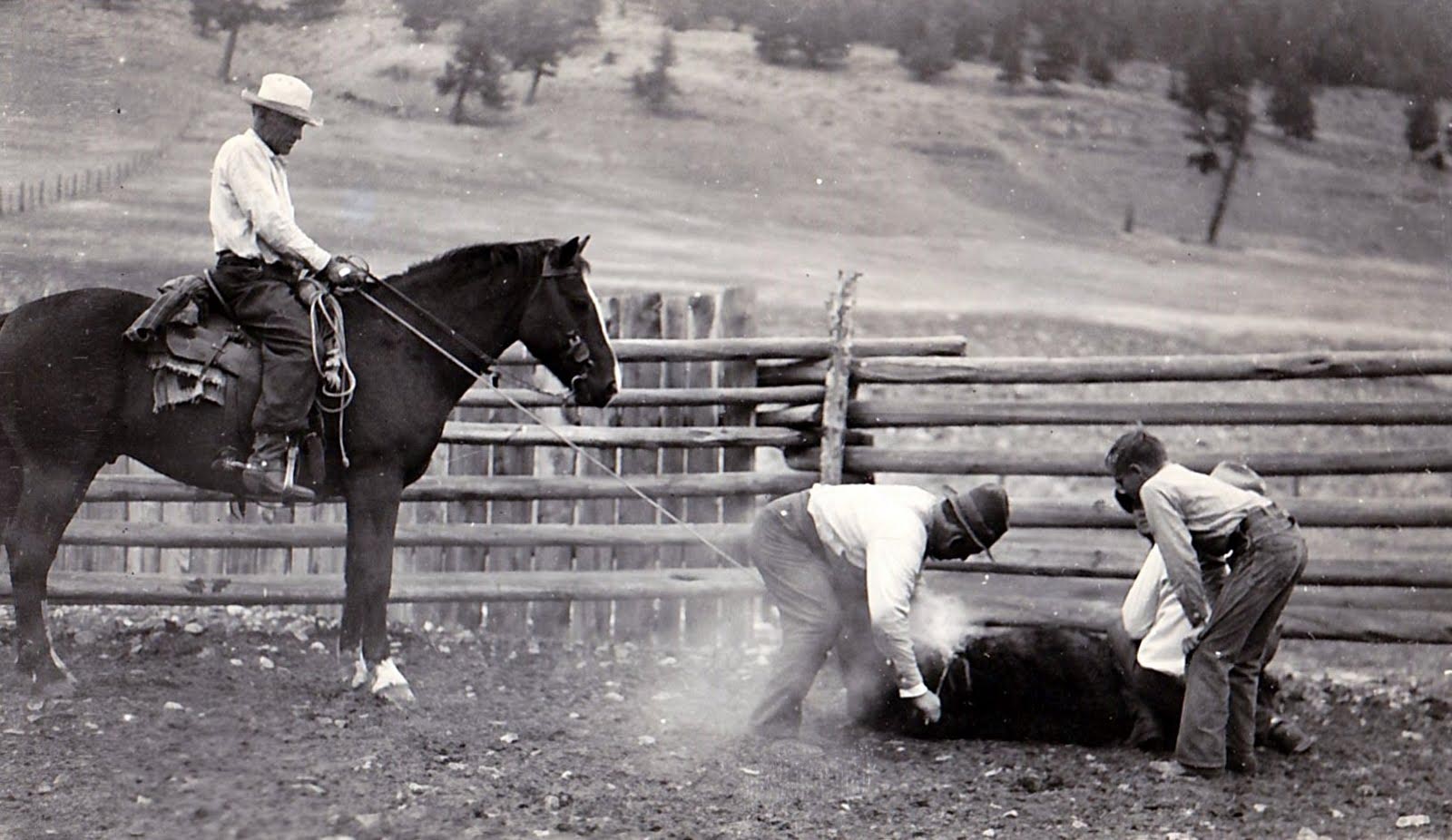

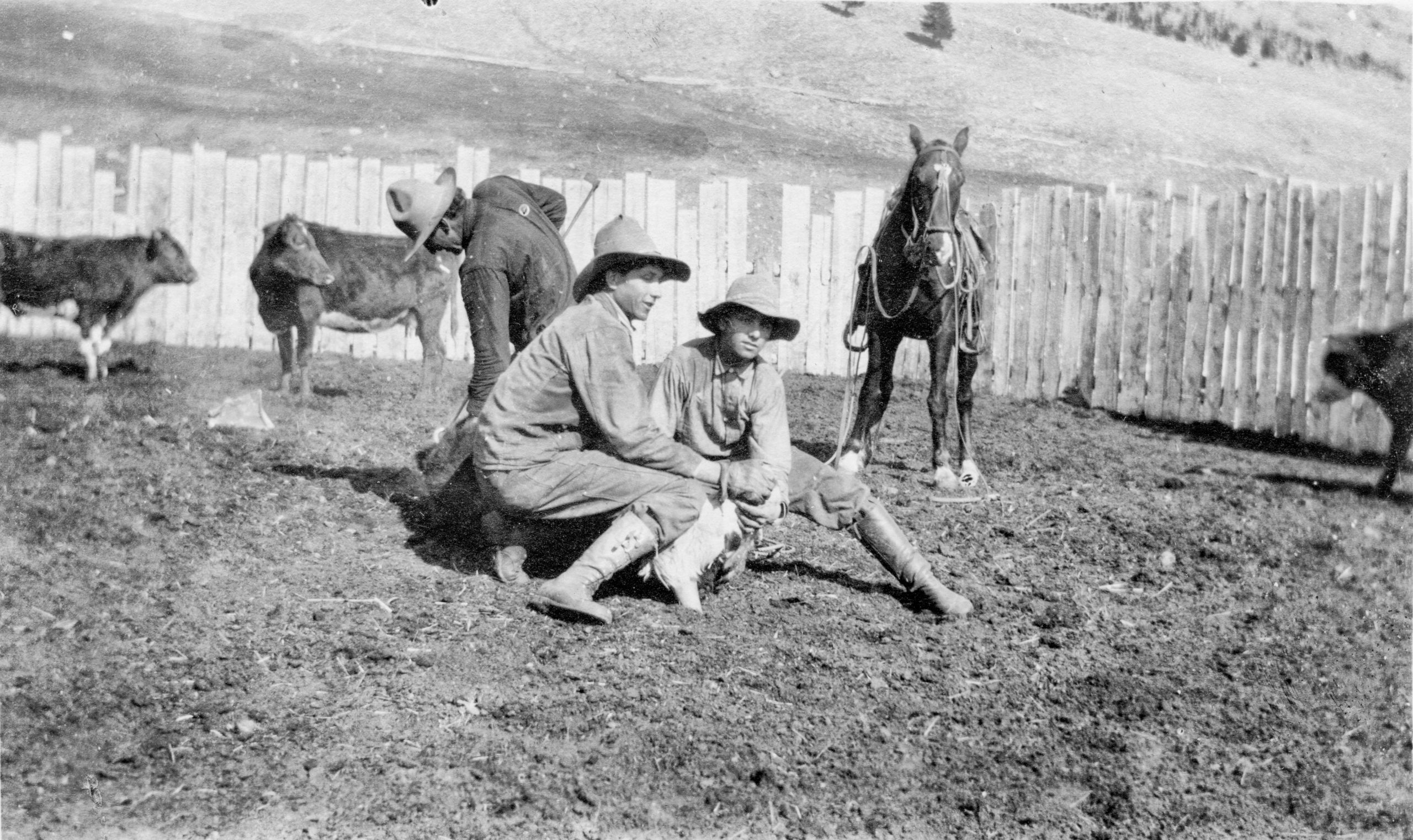

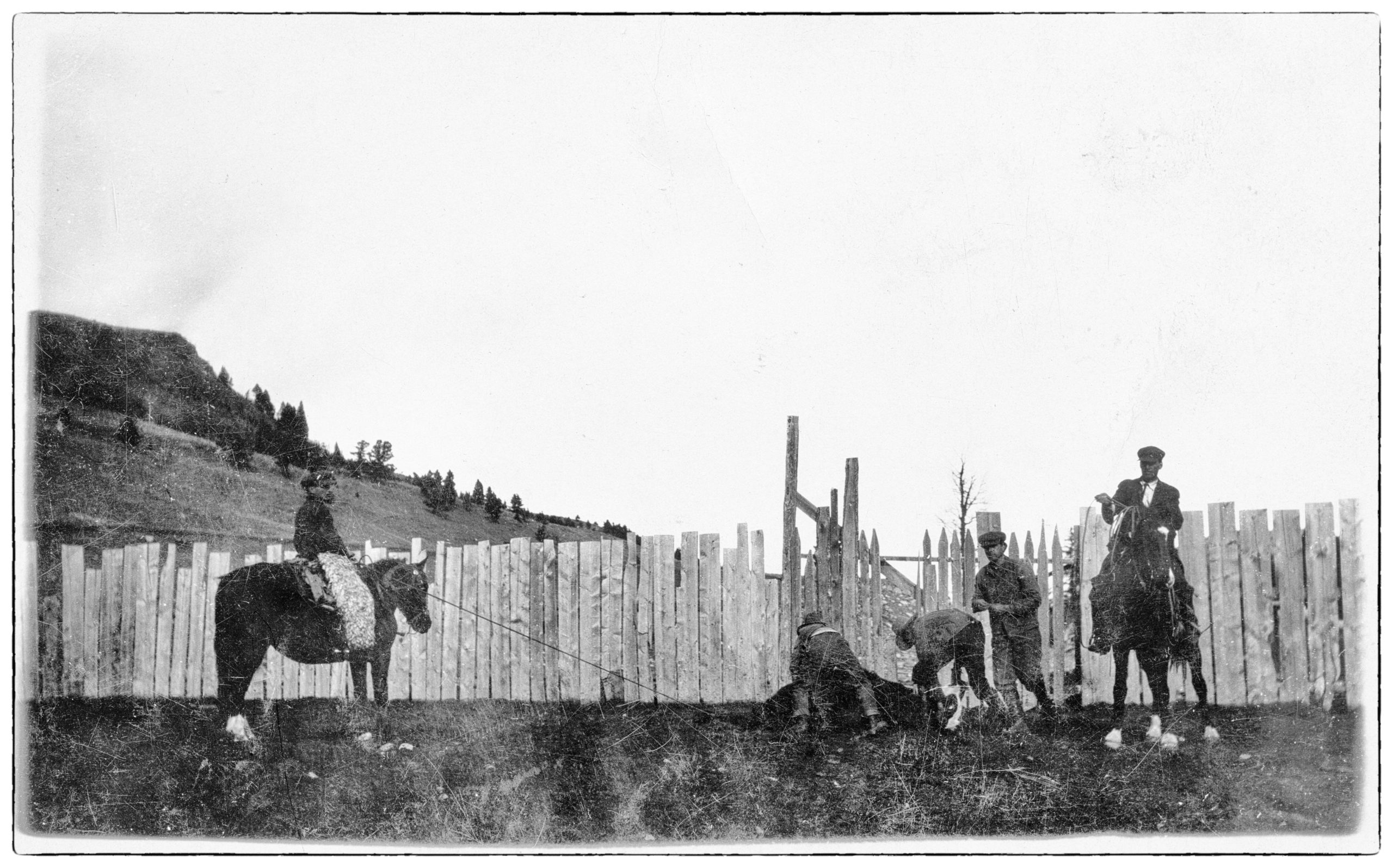

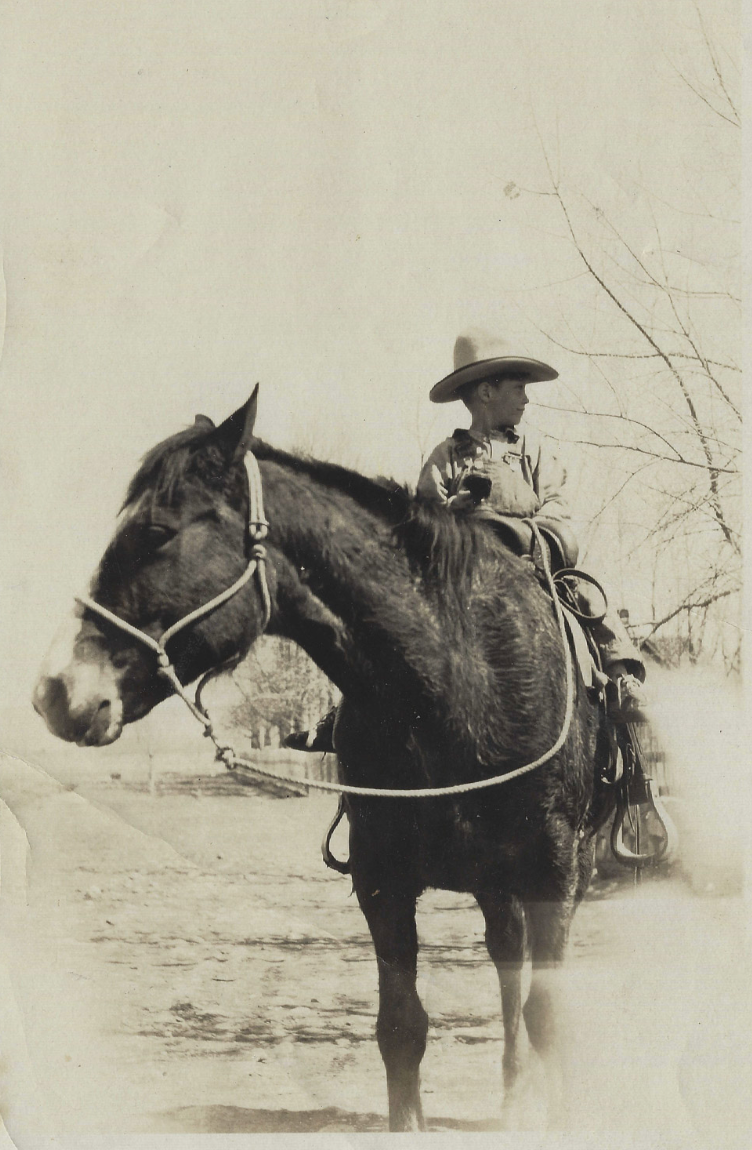

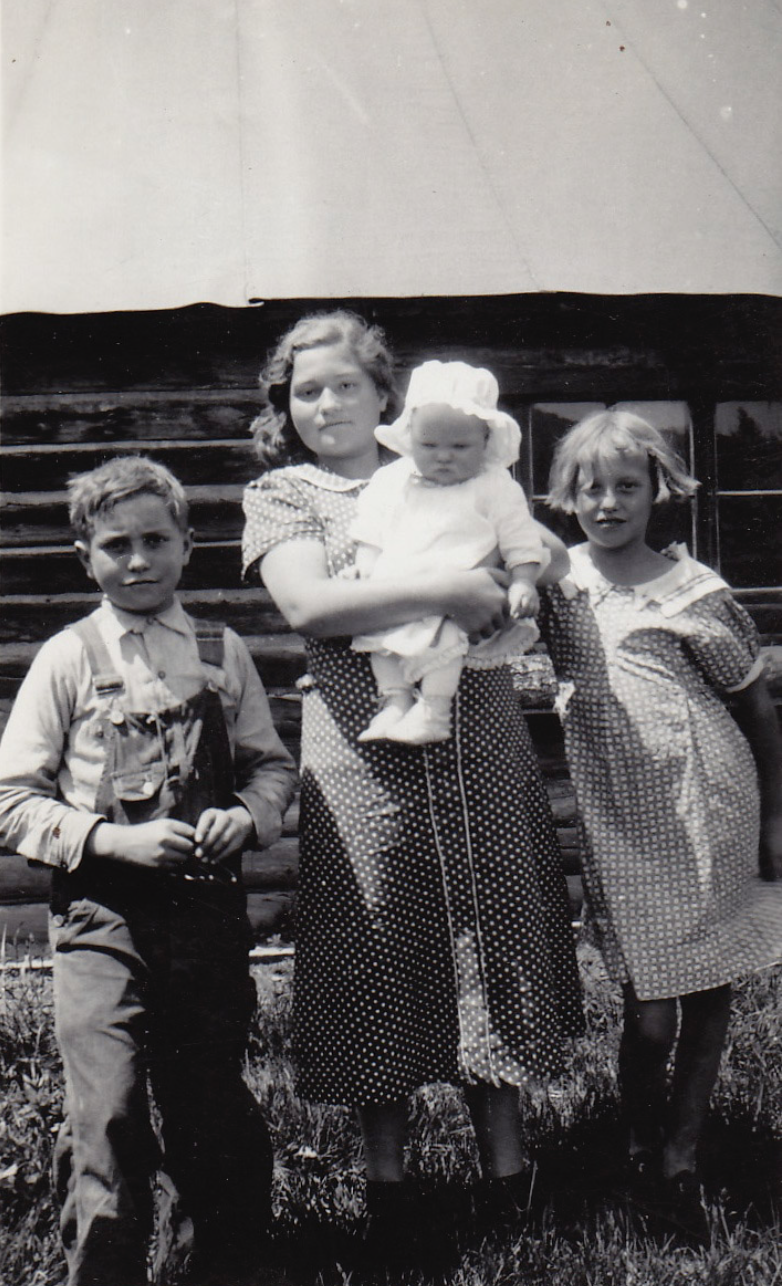

History lived there in the trees and behind rock piles along the trail. We heard it whisper old tales as we passed by. Laughter sang through the boughs of firs and pines as images of children played outside the old schoolhouse that once stood in the woods. If one knew where to look, there might even be faint visions of children pulling on the reins of the horses that stomped their hooves and swatted flies with their tails. Kids hid behind sagebrush while one rode an imaginary horse that looked like a dried-up stump. In the distance was the sound of the shrill whine of a sawmill. Smoke rose from the chimney as a greeting to any that made it that far into the heart of the mountains.

Though no one had lived at the place at the end of the road for some time, memories still lingered. As we pulled into the yard, we were greeted by Quaking Aspens waving their shimmering leaves in the summer light as if anxiously awaiting our arrival.

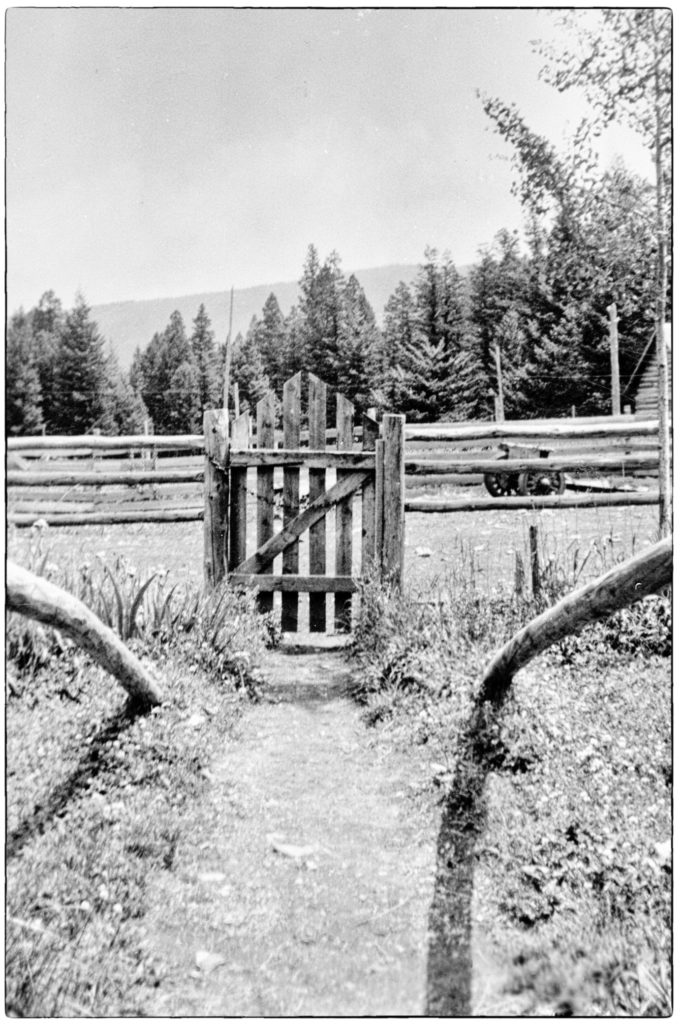

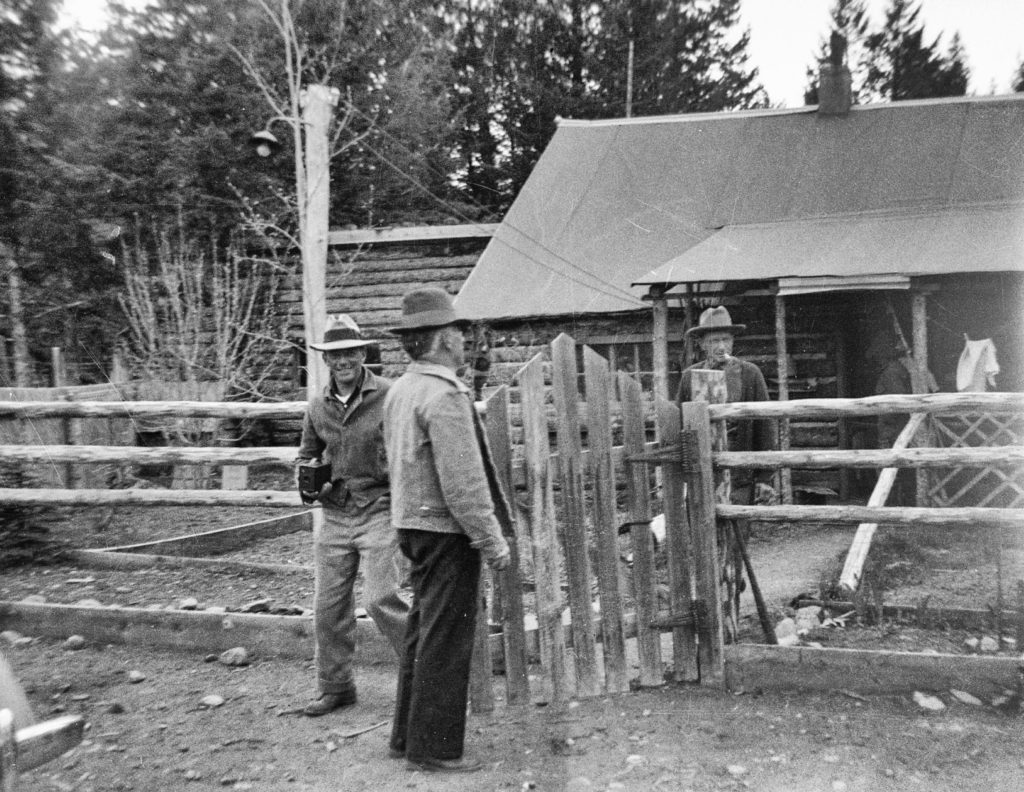

An old fence that at one time surrounded and protected the log cabin was all but gone except for a few worn pieces of wooden rails scattered on the ground. A weathered gate cheated time and stood defiantly in its place. Its rusty hinges gripped tightly to the posts that held the gate. Patches of faded green paint clung stubbornly to the brittle slats. A round piece of old machinery chained to the gate hung heavily to keep it closed and to signal the comings and goings of family and friends. Though I could have easily walked right past the gate, I opened it anyway and was not disappointed to hear the clang clang as it slammed behind me.

I stepped onto the walkway that led to the sagging door of the cabin. As I entered the doorway, a light breeze stirred remembrances along with the dust and dirt that danced across the floor with a breath of the wind. Memories came to life.

Thoughts and images flashed before me and soon the chill in the air dissipated. I looked around and was amazed at what I saw in my mind’s eyes. The wood cookstove was fired up and the cabin filled with warmth. On the kitchen floor was a washtub filled with hot water where a teenaged girl had just soothed her aching muscles after her trek in the mountains. At the sound of the clank and clang of the gate, weary backpackers trudged down the walkway into the house to be relieved of their burdens and greeted with the aroma of meat and potatoes cooking on the old stove. After dropping their packs and other gear, some plunked down on the long wooden bench and rubbed their aching feet. Some backed up to the crackling fire under the watchful eyes of the old deer mount that surveyed the scene with the shifting eyes of a sentry. At another glance, I saw little girls sipping hot tea out of fancy teacups with their grandmother. The slam of the gate caught my attention again as kids ran in and out of it as they played.

I think those who went through the gate just liked to hear that resonating tone, for you see, it signified something greater than just a clanging clanking noise. It symbolized hospitality, an ever-encouraging word, family, friends, love, laughter, and tales of life in the mountains. It meant safety, and protection from the rest of the world.

All too soon, it was time to go. The gate clapped one last time as it closed behind us. With one look back at the place in the mountains that had once teemed with life, I knew that on another day, we would make that journey again.

Though the green wooden gate no longer stands in the mountains, it remains a portal to a place of serenity, a place to recharge, and a place to visit in my memories when all else in the world seems wrong.