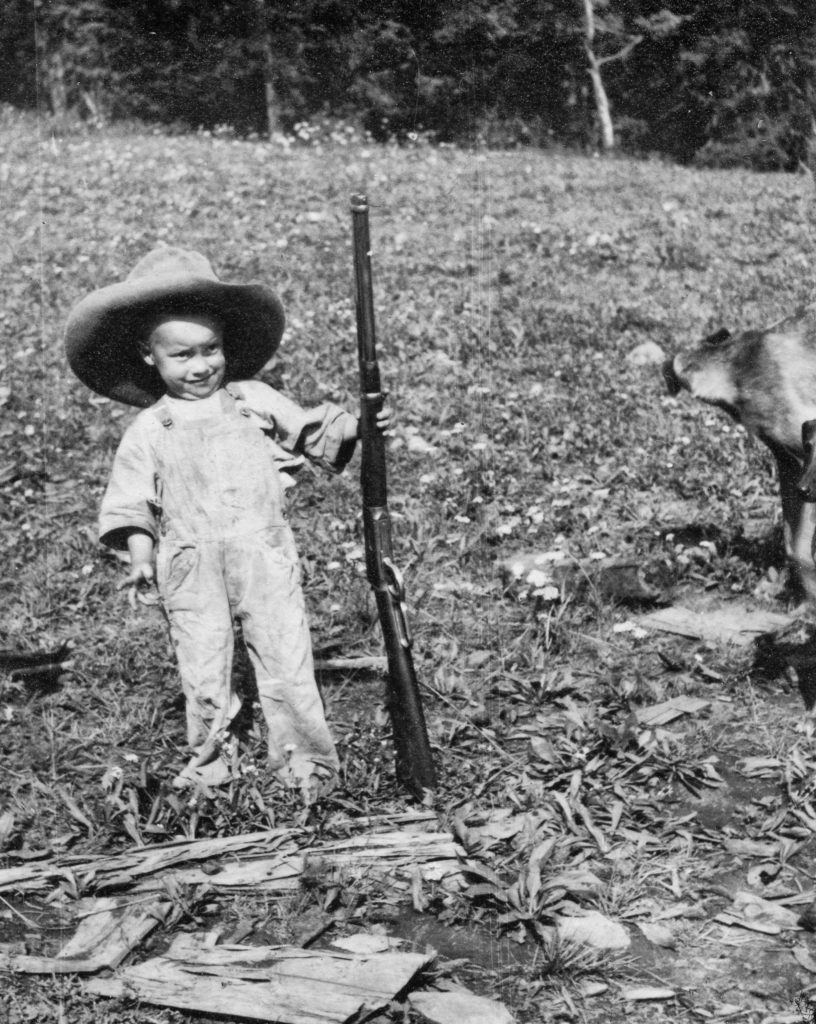

My Guest Author, my dad, said, “both scars and joys were imbedded in my childhood memories.” He often told this story a “stray kid in the early thirties when folks were too poor to nourish lice.”

Father was delivering a load of lumber when he saw a hitchhiker beside the country road. The hiker was about half grown, but his hands, feet, and nose were fully grown. His sunburned neck climbed out of a ragged shirt and his Adam’s apple made a small shelf more sunburned that the rest of him. The young man said that he had left home in Wyoming because his widowed mother didn’t have enough money to feed her family. For a week he had been hitching across the prairies of eastern Montana. Then somebody told him he might get a job on one of the mountain ranches west of Melville. That’s where Father picked him up.

Maybe it was because of the boy’s story. Maybe it was because his oldest son was confined to bed and needed company. Maybe it was because Bud Ward was that kind of a man. Whatever the reason, Father brought the hitchhiker home. He introduced him as “Jimmy Hicks”. This wasn’t his real name. It was a name born out of depression times. It symbolized a wandering youth in search of a place to stay and a place to work.

That night Alan Storm threw his spare shirt and blue jeans on a bed in the bunkhouse. He came into the kitchen with the hired men and sat down to a square meal. His sunburned Adam’s apple bobbed up and down. For a skinny kid, he sure knew what do with food.

When it came to work the new hired hand wasn’t very experienced. He chopped into rocks, fastened chains to logs the wrong way, got lost on the mountain and broke his ax handle. When he carried in an arm load of stove wood, he stumped his toe and scattered sticks all over the floor.

After the first month, Ernest Parker summed up the situation. “By the Great Horn Spoon,” he said, “that kid will never make a lumberjack.”

Some of the neighbors wondered how long the Hicks kid would keep his job. But two and three months went by and still Jimmy Hicks stayed on. His body was filling out, but he continued to dull his ax and get lost. However, Jimmy had jobs that the neighbors did not know about. In the evening, after work, he would get on his hands and knees on the lawn and I’d sit astraddle of his back and use him for a bucking horse. When he was bucked out, even Sister Barbara could ride him without pulling leather. After supper, Jimmy would sit in the middle room and talk to my brother. There was about two years difference in their ages.

Brother Jack had lost the use of his legs and paralysis was creeping up his body. He had received more x-ray treatments in Billings. His hair had fallen out again, and the doctors said that nothing could be done to stop the growth of the tumor in his brain. But in the evenings after supper, laughter resounded from the couch in the middle room.

Just like I’d find out in later years, giants and angels come in all sizes, and when you entertained one, you didn’t know what would happen. There would be good things to remember. In the next decade there would be sad things too, for a battlefield at Salerno Beach in Italy would cut short any more memories about a stray kid we knew as Jimmy.