Stars twinkled across the sky from one side of the prairie to the other. It looked as if they had been cast into the black of night to hang by a thread. They swayed and lit up the world below as they illuminated the path of stardust across the Milky Way.

Fiery red and yellow flames danced against the night sky in rhythm with the twinkling lights and the music that glided on the breeze. The crackle and pop of the fire added percussion to the tunes that rose and fell from the stringed instruments.

After days on the trail, the evening fire under a clear sky was a reprieve. Not only had there been some days and nights of rain when everything got soaked, but they were travel weary. Oh, there were times when they stayed in camp a couple of days when they camped beside a river. That’s when they repaired harnesses, wagons, and equipment, did laundry, cooked a big pot of beans, and swam in the river. But a cool crisp evening around the fire was a special treat.

Sitting around the fire was a diversity of participants and onlookers. Dad Knapp with his fiddle, and his son, Bee, who played the fiddle he bought from Old Man Bradley for $12.00 a few years earlier, drew their bows across the strings to release the rich mellow tones. Someone else grabbed the banjo, while another tried to add to the tune with a mouth harp.

Those who sat in the warmth of the flames were diverse as well. A toddler was in the arms of Mother Knapp. Little Evelyn sat wide eyed, not wanting to miss a thing. Bee, at seventeen, was the oldest of the children on the trail, brother Fred having stayed behind. He and Buster drove one of the teams. Leone usually rode with the brothers though her eyes were set on the shy handsome young man who helped Uncle Press with his wagons. The McNeil cousins, one Evelyn’s age, added to their companionship. More than just family shared their fire as well. Travelers they met heading east pulled out their instruments to join in the revelry. It is said when Dad Knapp played the fiddle, even “a wooden Indian couldn’t have kept his feet still.” No less could the Indian braves who joined their fire on the open prairie as they neared the Crow Reservation. The braves found great entertainment with the pioneers but also wanted to try to work a trade for Bee’s big bay, Bill, that had outright beat their Indian ponies in a race. They offered five ponies for the bay whose veins ran with race blood. Bee would not strike a trade.

As I peer through the curtains of time, I see Indian braves and children dancing around the fire, the braves trying to coax Leone to join in the dance, smiles and joy reflected on faces in the firelight. I hear the music of the instruments playing old dance tunes with laughter and singing rolling across the prairie like tumbleweeds. Somehow, I sense that Dad Knapp especially was completely content.

He thrived in the wide-open countryside. When neighbors moved too close, he felt penned in. He was among the rushers into Indian Territory in Oklahoma 25 years earlier. But things were getting too crowded for him. By 1914, word came of new territory. Montana was open country. There was land a plenty. A couple of the McNeil brothers had already staked a claim with glowing reports of good grass and plenty of land, 320 acres per homestead. That was enough for Dad Knapp to pull up stakes. Their success depended on the Oklahoma harvest. One hundred acres were planted in wheat. They could easily lose a crop to locusts, drought, hailstorm, or prairie fires. So much hinged on the weather, they were nervous and anxious until the time of harvest came. Dad Knapp didn’t care for the storms that rose up without warning on those western prairies. With an eye on the weather and a prayer on their lips, they waited. The time of harvest came and brought a bumper crop. It was enough for them to make the move.

They arrived at their final destination sixty days and over 1300 miles after they began. The following spring, the families all moved to their prospective homesteads. That was wide open country that seemed as vast as the endless sky – enough to satisfy the wandering soul and itchy feet of a prairie fiddler.

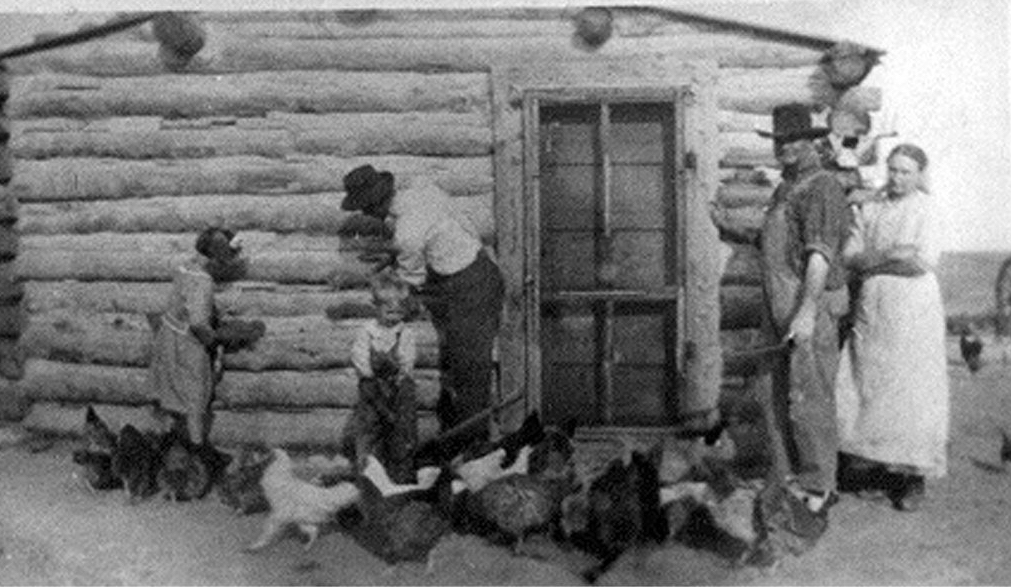

Knapp homestead on the Montana prairie, Evelyn to the left

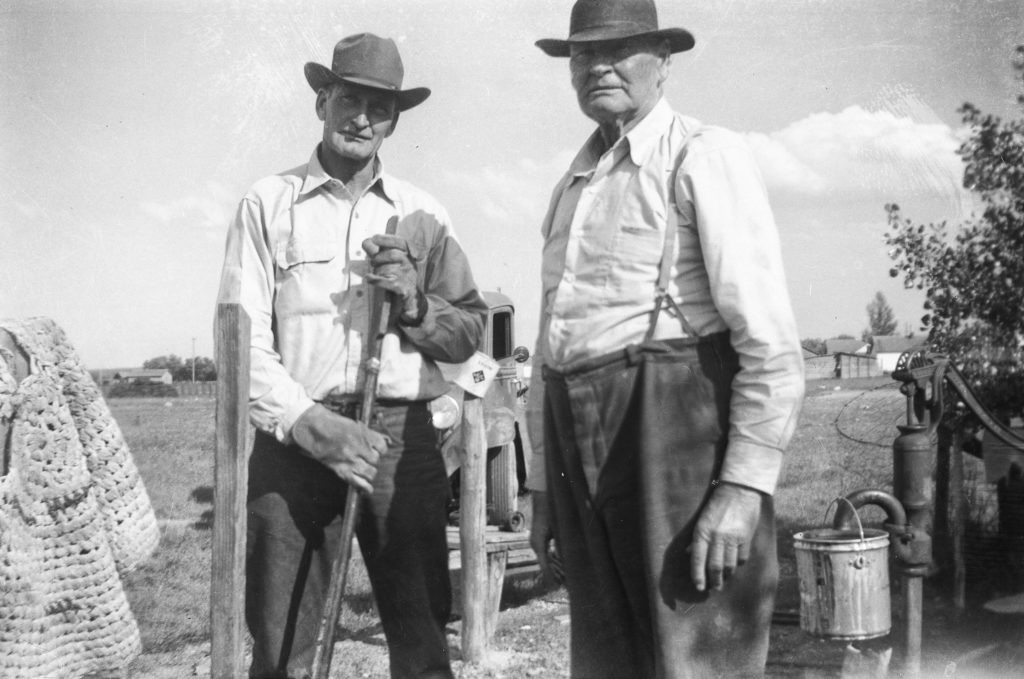

Years later, Charles Knapp retired in Big Timber, Montana

where he lived out the rest of his days.