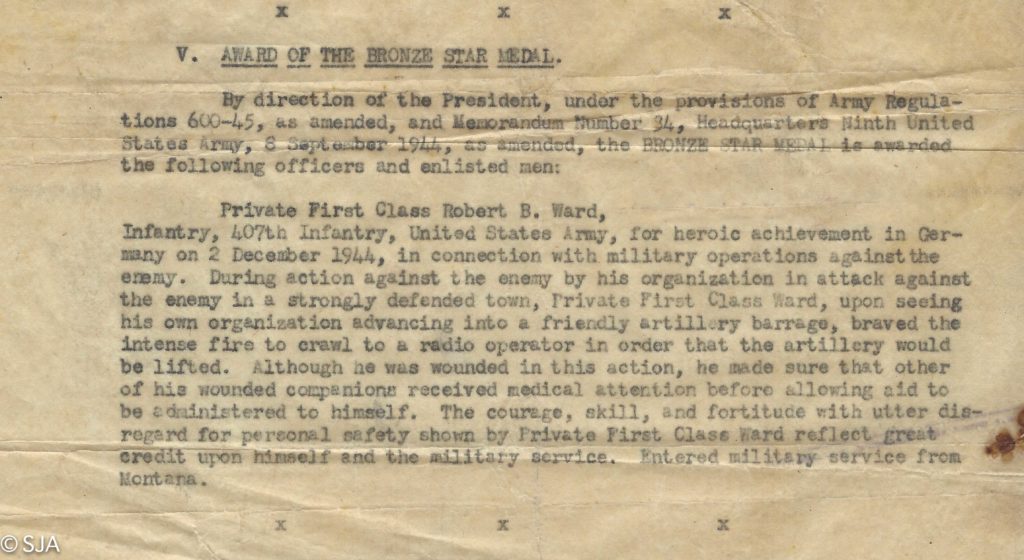

Lieutenant Donald Lovell

died December 15, 1944

Artillery shells screamed as they fell like rain. Some hit the ground but never exploded. Others burst without warning. The flat open fields near Flossdorf made the soldiers open targets for machine gun and rifle fire. Bullets sprayed the ground. Artillery was hidden behind a low hill that overlooked the beet field. The enemy aimed for the legs of the soldiers as they ran across the open fields. Some were hit. Caught in a barrage of fire, Lieutenant Lovell called for “Little One” to “get them to raise the artillery.” Pvt. Ward got the radio message through. The enemy unleashed everything they had. “Little One” was knocked to the ground by something that felt like a sledgehammer in his back. He fell back into the shell hole where his Lieutenant lay. The Lieutenant had been hit with the same blast. Pvt. Ward bandaged the Lieutenant’s legs the best he could. He reached for the boot that lay ten feet away. Part of the Lieutenant’s foot was still in it. Pvt. Ward stuck the rifle in the ground, bayonet down, so the medic was alerted that a soldier was down. He then gave the Lieutenant his sulfa pills and threw his raincoat over the bloody legs. He managed to dig the hole deeper then went for help. The word went down the line. Lieutenant Lovell was taken off the field that day but he did not survive the conflict.

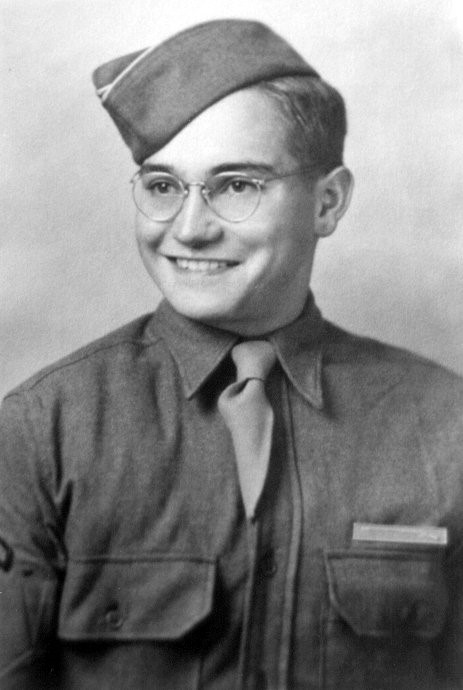

Pvt. Ward heard another call from the beet field behind him. A soldier from F Company, Pvt. Leo Halash, was lying in the field. His helmet was sticking up among the beet tops. Every time he moved, a bullet whistled over his head. Pvt. Ward bellied his way to the wounded soldier. A bullet had torn a hole through the soldier’s leg. Pvt. Ward bandaged the wound and gave him his wound pills. He used a belt as a tourniquet and then dug into the ground for a trench deep enough to get the wounded soldier below the ground. Again, he jabbed the bayonet end of the rifle in the dirt to signal the medic. The trench wasn’t deep enough for two, so Pvt. Ward crawled away, hoping his helmet would deflect shots that came his way. He crawled sixty feet toward a voice that called to him from a foxhole. He slid into the hole with Robert Kendall who administered sulfa pills to Pvt. Ward, bandaged the hole in the back of his ribs, and covered him with a raincoat. Robert Kendall lost his life shortly after that action.

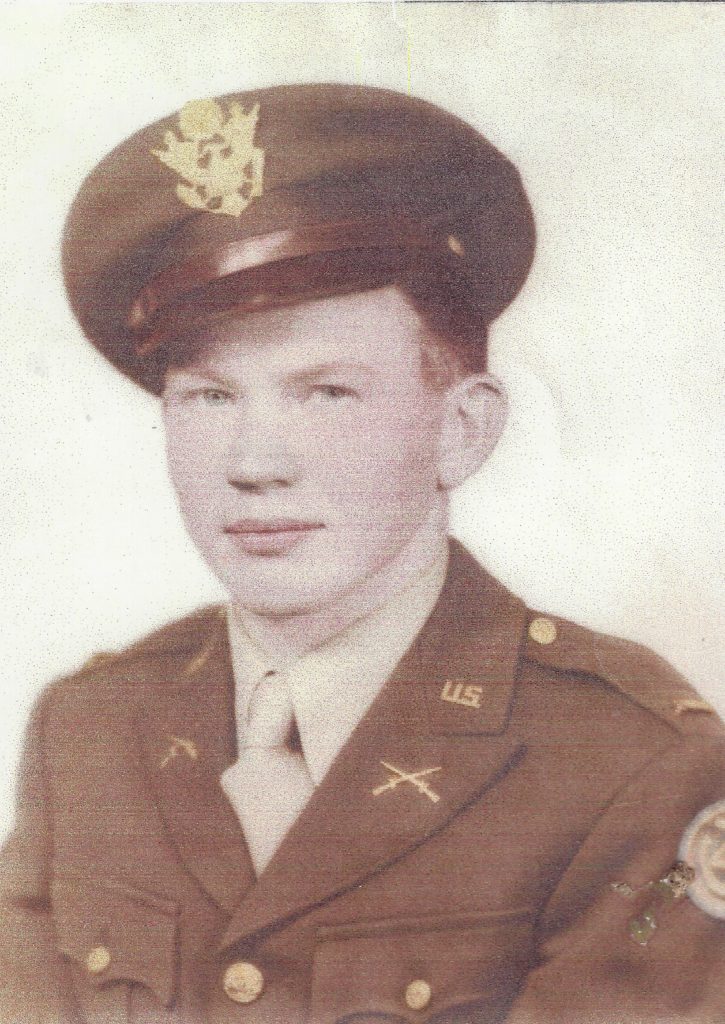

Robert Ward

Leo Halash

Pvt. Halash did survive. He spent countless days in hospitals fighting to keep his leg. For two and a half years, he was in VA hospitals. He steadfastly refused amputation and underwent numerous bone and skin grafts and various treatments. He kept his leg despite being stricken with osteomyelitis but walked with a limp and couldn’t bend his knee. Back home, he married and had seven children. A heart attack claimed his life in 1971 at the age of forty-six, but that’s not the end of the story.

Years later, in 2016, Robert Ward received a call from the Library of Congress asking permission to give his phone number to someone in the Halash family. They had found the story of the events of December 2, 1944 as told by Robert Ward. In no time at all, the call came. One of the sons of Leo Halash thanked him for saving his father’s life. Other calls came from other family members including the wife of Leo Halash. Soon a letter arrived from Mrs. Halash. Robert Ward said, “I didn’t do anything. The belt saved Leo’s life.” It was the soldier’s quick thinking, his passion for life, his willingness to sacrifice himself, love for his fellow man and his available hands that saved Leo Halash’s life. God placed him there that day.

Not long after that, Robert Ward spent some time in the hospital. He received a letter from the Halash family. When I handed it to him, he asked me to read it because his eyes were blurry. By the time I was done, he had silent tears sliding down his cheeks. He recounted the story of December 2, 1944 again. That time, he gave a fresh description of the incidents of that day, even telling how the enemy weapons were lined up low at the edge of the field. It was like he was seeing it all over again, adding descriptions I had never heard before. He showed me where Halash was wounded. He described the kit he carried with the bandages and pills and gave the step by step administration of those:

“I gave him his pills and I bandaged his wound. If I had not put the belt on his leg, he would have bled to death. But time was critical. If the tourniquet was on for too long, he would lose his leg. It had been raining so I was able to take the claw-looking tool and dig into the soft ground. I don’t remember the first time I saw Leo Halash, but I sure remember the last time. When it was all over I looked through the list of casualties and didn’t find his name listed among the dead. So I knew he survived.” He said, “For over seventy years I have had flashbacks on December 2. I see Frank Svoboda. I see Lieutenant Lovell lying on the ground – wounded – and his detached boot with his foot still in it. I see others who lost their lives. I see a soldier in the field and hear him call for help. I hear enemy fire all around.” A tear escaped and he continued, “But now I have been given a good flashback. After seventy years, I can now see life – that of Leo Halash. I thank God that I was there that day and that Leo survived and had a good family. That’s a good flashback!”

Pfc. Halash and Pfc. Ward were both recipients of the Purple Heart and Bronze Star. They also studied at Purdue University at the same time where they saw one another in passing, not knowing that their lives would cross paths so intimately on the battlefield or that their stories would be intertwined.

Some call my father a hero, and that he is. But I find other heroes in this story – those who gave their lives in the line of duty – those who administered aid to their fallen comrades – those who fought for our freedom. Another hero emerges as well. The family of Leo Halash is my hero. They brought closure and gave an old soldier peace after seventy years. For the first time since December 2, 1944, he did not have flashbacks on the anniversary date of the battle. Memories that rose from the ashes of loss and death were met with hope and a smile.

You can read more of the Winter of ’44 as told by Robert Ward

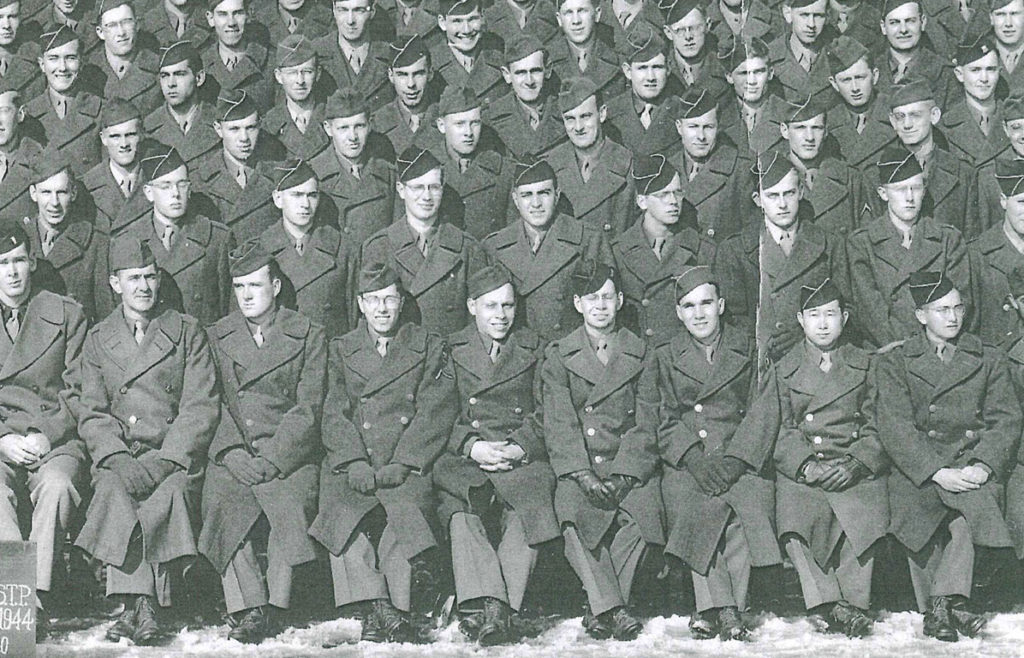

Pvt. Leo Halash, 1st on left, row 2 ; Pvt. Robert Ward, 1st on right, row 1