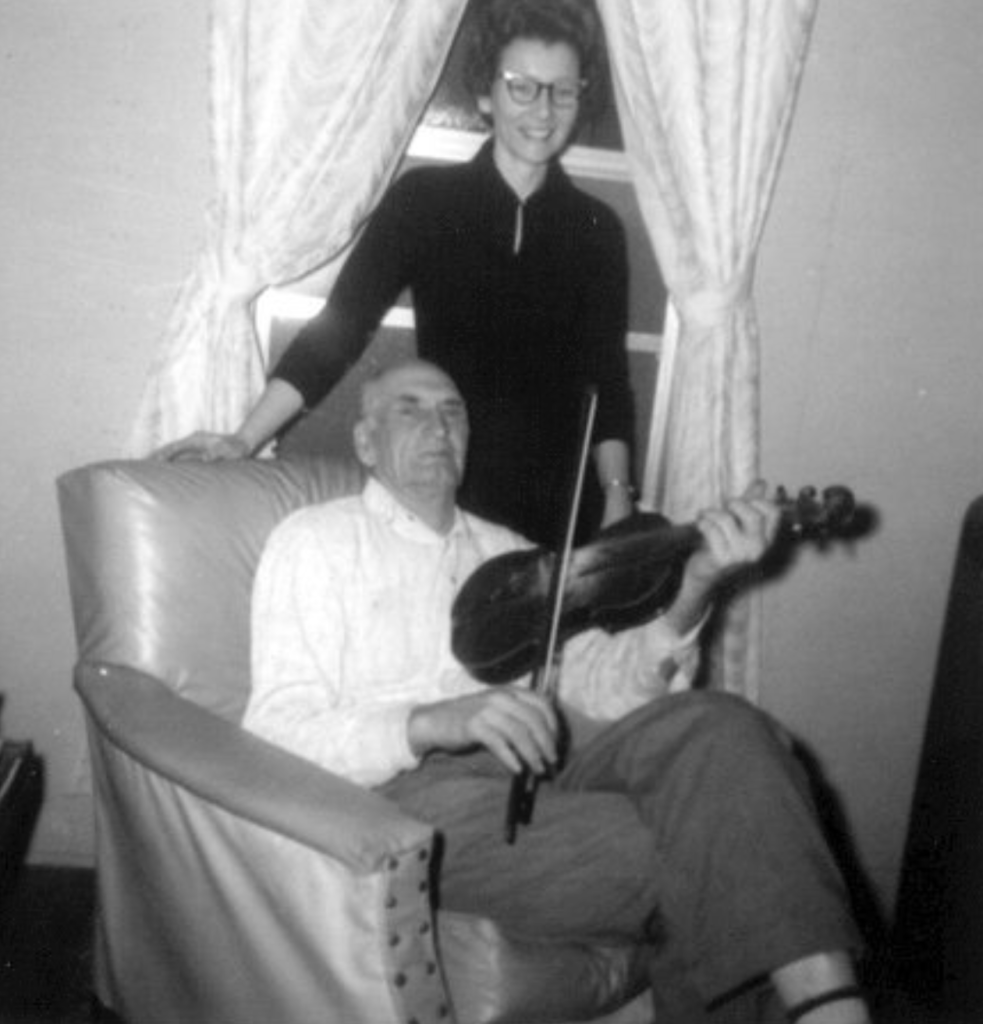

My Guest Author, my dad, grew up where the magic lives

The sky was covered with storm clouds. The January day was short without the thick clouds blanketing the afternoon light. Snow had been falling for the last two hours. Now, the wind was whipping it across the long open flat. The horses faced into it. The family huddled in the wagon. The heavy robes, made from Angora goat hides, failed to keep out all the cold.

At times the wagon trail was wiped out. The Thompson hills had disappeared. The mountains behind them were blotted out. The team moved slowly ahead. They knew the way even when they could not see the ground ten feet ahead. They stopped at a gate in a barbwire fence which stretched from the hills on the left to the drop off in the canyon on the right.

One of the boys opened the gate and the team plodded through. They had three hours to go. The light was gone.

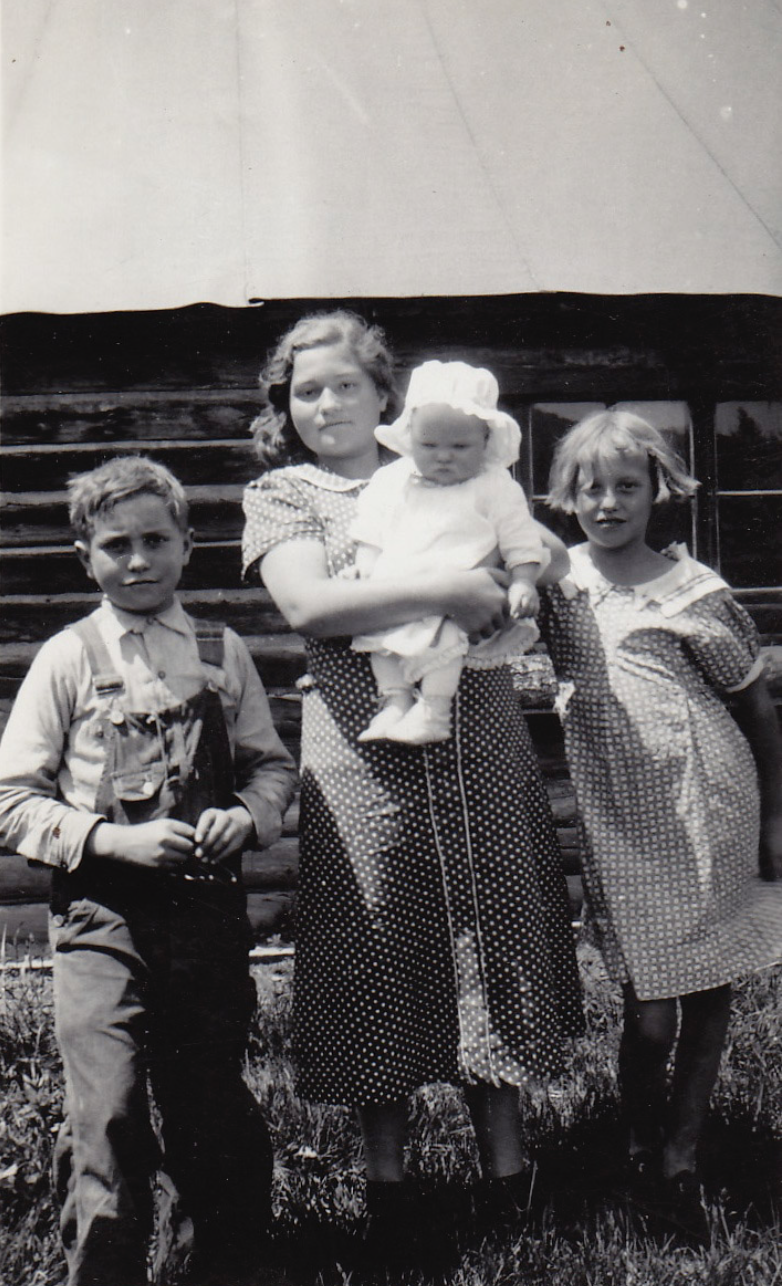

More than the light was gone. The woman fought against a quiet despair made worse by the howling blizzard. Her husband was gone.

The children were not gone – the wagon was full of her children. The older boys, now grown into men, took turns facing the wind while the others covered themselves the best they could.

That was the way the day was ending. That was the way the week was ending. If she had any tears left Guadalupe Brannin did not share them at this time.

Her husband was dead. He was gone.

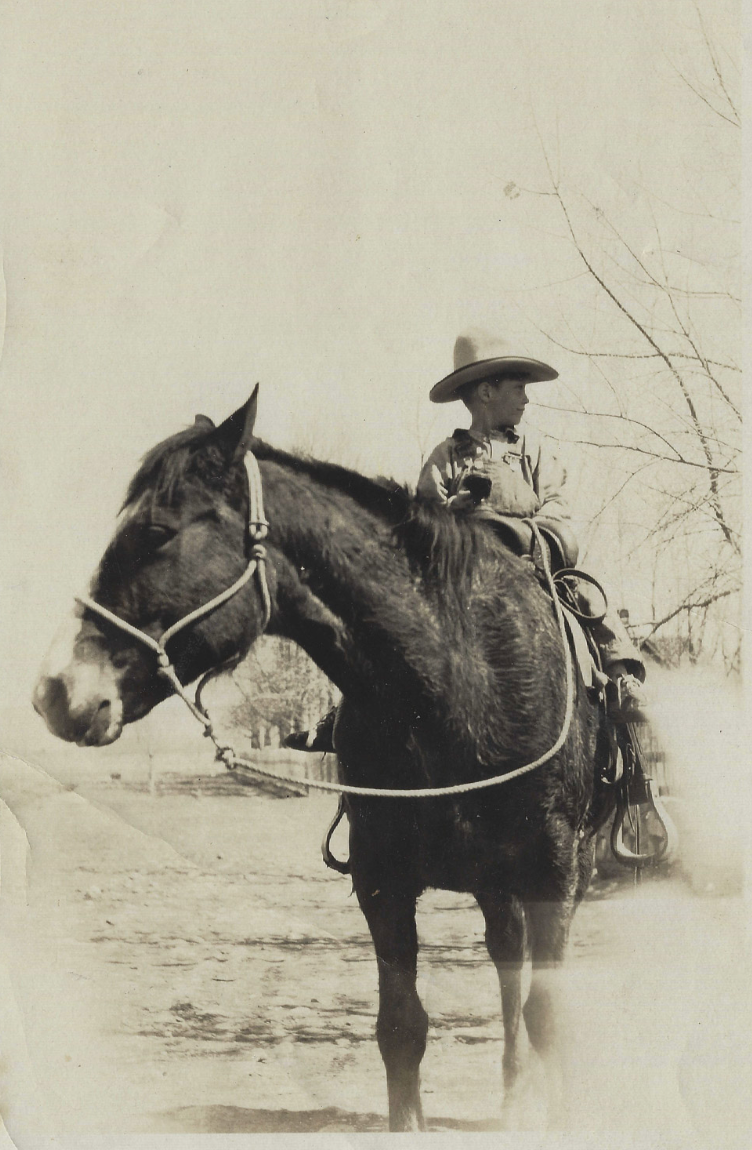

She had a foreboding of that when he left some weeks earlier to get to a town with some medical help. He had on his corduroy trousers. The crown of his hat was pushed down in Texas style. He rode old Bob. He’d been invincible, but now, the invincibility was claimed by a grave on the far side of town thirty miles back and across the river.

“Mama,” one of the boys said, “Mama, we’re in no shape to make it home tonight.”

The Grossfield cabin was just up ahead.

“We’d better stop.”

The team pulled off to the right where a log cabin huddled against the rolling hills. A dog barked a welcome from his nest in the barn. The door of the cabin opened. Abram Grossfield looked like an angel from heaven, and the family came in out of the storm.

They would remember that night. They would remember that there was a welcome after a storm, that there was hope after a graveyard.

The fire was warm. The children were fed. Condolences were given. There was talk of the mountains and the news from the settlement. And the house was warm.

The next morning the storm had eased up. The wagon was loaded. The team plodded up the draw and over the hill that broke down to the Sweet Grass. By then the sky had cleared. From the top of the ridge Guadalupe Brannin looked down into the mountain valley. She saw the log house on the far side of the valley, and the root cellar that the boys had dug into the hillside just in time to hold a wagon load of potatoes for the winters supply.

She’d been there only two years, but this was home, and home is where the magic lives.