That September day one hundred twenty-five years ago, Doctor Bezalell Bell Andrews arrived to make a special delivery. The next morning the Knapps welcomed another baby boy into the family. Dr. Andrews handed the baby boy to his mother and said, “Bee Bell. That’s his name, named after me. When he gets bigger, I’ll give him my silver watch.” The baby’s father wanted to name him Jack, but his mother said, “The doctor has already named him. He’s Bee Bell!” The Knapp family moved from Nebraska before little Bee was old enough to carry the promised watch, but he did carry the name with him all of his life. That in itself was a tremendous gift and extraordinary honor.

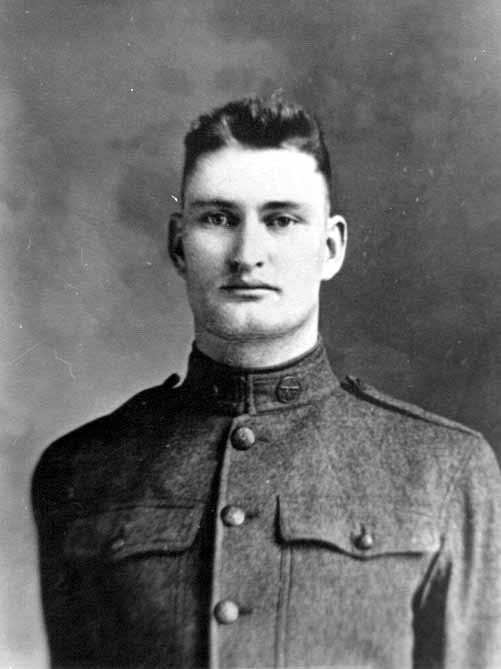

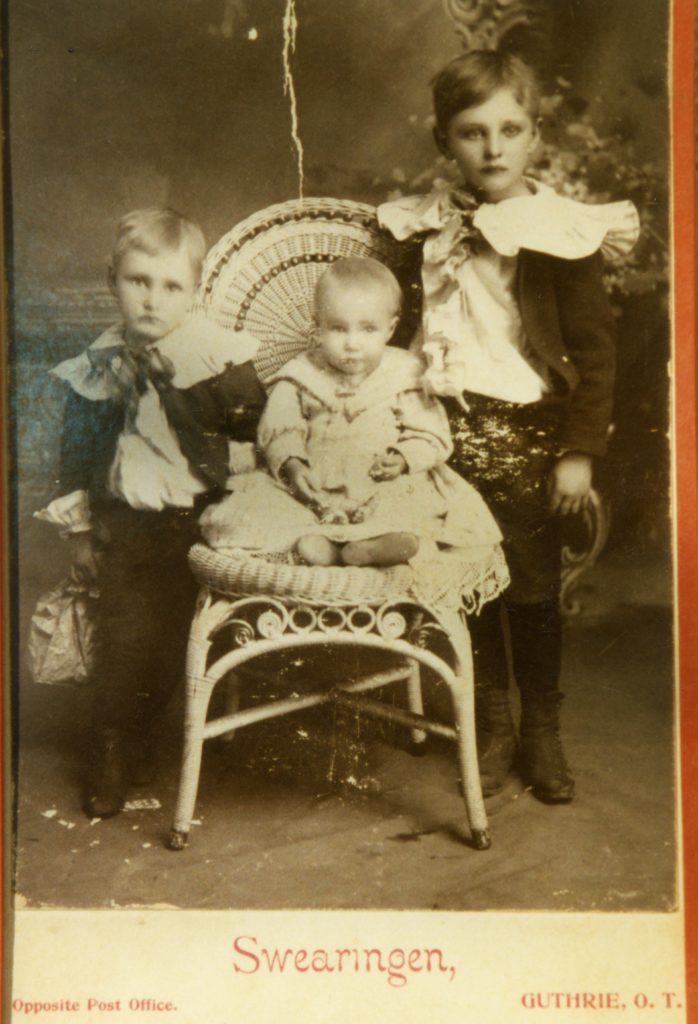

Bee Bell Knapp with sister Leone and brother Fred

Bezalell Bell Andrews, commonly known as B. Bell Andrews, was no ordinary man. His patients and community knew him as a respected physician and surgeon. He practiced medicine, which included homeopathy, in Stella, Nebraska for a number of years. His wife was also a doctor. But there was more to Dr. B. Bell Andrews. More than thirty years before the delivery of a baby boy on that 29th day of September, 1896, Bezalell Bell Andrews was a prisoner of war.

While serving with Co L 17th Illinois Cavalry, Andrews was captured at Jonesville, Virginia on January 3, 1864, and sent to Belle Isle, Richmond, Virginia. In February, the prisoners on Belle Isle were moved to Andersonville, Georgia. It is said, “The men who left Belle Isle were dirty, poorly clothed, and almost all of them weighed less than 100 pounds.”

Upon arrival at Andersonville, Andrews (aka Lale) was taken into a building where his chum, John McElroy (aka Mc), saw him. That may well have been the salvation of both of the teenage boys who were thrown into manhood in one fell swoop. McElroy, who became a journalist and author, later wrote of their experiences at Andersonville as well as the other camps to which they were moved before being released.

McElroy told of his initial arrival at Andersonville, “Five hundred weary men moved along slowly through double lines of guards. Five hundred men marched silently towards the gates that were to shut out life and hope from most of them forever. A quarter of a mile from the railroad we came to a massive palisade of great squared logs standing upright in the ground. The fires blazed up and showed us a section of these, and two massive wooden gates, with heavy iron hinges and bolts. They swung open as we stood there and we passed through into the space beyond. We were in Andersonville.”

The two friends stayed together and managed to gather a few items including a couple of tin pans, a few pieces of lumber to construct a shelter, a few onions and collards from a garden on the side of the road, and a few garments stripped from the dead. They shared a coat and a blanket, huddling together for warmth.

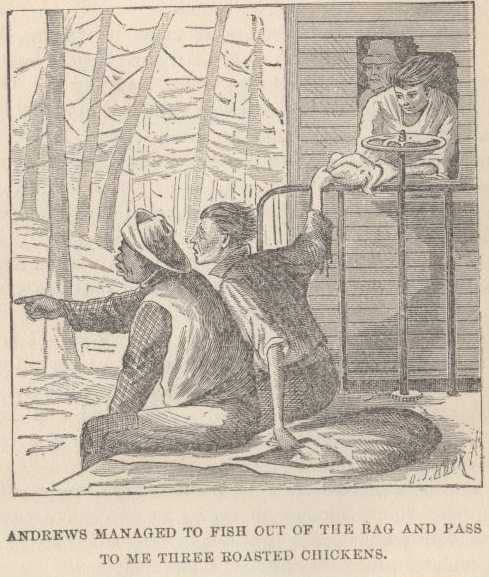

Andersonville : A Story of Rebel Military Prisons

by John McElroy, 1879

One of their prized possessions was a crudely made chess set. Here is McElvoy’s account, “My chum, Andrews, and I constructed a set of chessmen with an infinite deal of trouble. We found a soft, white root in the swamp which answered our purpose. A boy near us had a tolerably sharp pocket-knife, for the use of which a couple of hours each day, we gave a few spoonfuls of meal. The knife was the only one among a large number of prisoners, as the Rebel guards had an affection for that style of cutlery, which led them to search incoming prisoners, very closely. The fortunate owner of this derived quite a little income of meal by shrewdly loaning it to his knifeless comrades. The shapes that we made for pieces and pawns were necessarily very rude, but they were sufficiently distinct for identification. We blackened one set with pitch pine soot, found a piece of plank that would answer for a board and purchased it from its possessor for part of a ration of meal, and so were fitted out with what served until our release to distract our attention from much of the surrounding misery.”

Whenever they were moved, they would gather up their crudely carved primitive chess pieces and board and wrap it up in a holey blanket as if it was the grandest and only possession in the world, pushing their way to the forefront. They wanted to be the first load of prisoners to be moved, hoping with the hope of a futile promise of being exchanged for Southern prisoners. They were human pawns in their own game of chess, using their honed wits and strategy to survive.

It is said that “War is Hell.” In this hell, teenage boys were forged into men. Here, a name was made, but Bezalell Bell Andrews was more than a mere name, it spoke of character, endurance, and determination.

Not only does history touch each of us in some way, but it is in our history that names are made and character is fashioned. The little boy named Bee Bell, born that fall day in September 1896, became my grandfather. He carried his name well, for he too was a man of honorable character with a heart of compassion.

https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/ander.asp

You can read a portion of John McElvoy’s interesting account of the survival of these two friends and the conditions they survived.