We were filled with anticipation as we walked through the doors of the Montana Historical Society Library. A lady brought out our family’s file full of treasures. As I sorted through the files of documents, love letters, and other interesting tidbits of information, my cousin went to inquire about another treasure we hoped to find. Another staff member came and led us out the door and down the stairs. In the basement, we found row after row of shelves filled with thousands of Montana historical artifacts and files. The lady stopped and pointed, “there it is.” There propped against the wall was a square rosewood Steinway piano, the keyboard and soundboard on their side with four legs resting in front. Above the strings on the soundboard was the number 1863. Was this really THE piano we had heard about in family tales from childhood? The lady who led us to the basement walked off and returned with a folder. Excitedly, I looked through the papers. There it was – proof that the piano was no myth and was indeed the one brought across the country by family members one hundred fifty years earlier.

My mind erupted with questions. What events brought the piano here? What would it have been like to hear an accomplished pianist play the ivory keys of the Steinway? Was there anything we could do to have the piano and its story put on exhibit?

The next few years, details gathered from various sources, including Montana historians and the Chief Historian at Steinway and Sons, came together. I became the spectator, and the story began to unfold as events of the last century and a half rolled back like scenes on a movie reel.

Shortly after coming to America, in 1853 Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg started his own company under the name of Steinway and Sons. He came a long way since he built his first piano in 1825 in his kitchen in Seesen, Germany, as a wedding gift for his wife. It is said he had an “inherent talent for music” and an “unusual mechanical ingenuity.” That was proven as Steinway pianos rose to fame. On May 5, 1857, Steinway received his first of many patents, this one to improve “smooth repetitive action” of the keys. According to the Chief Historian at Steinway and Sons, that same year (not 1863 as family records stated) a piano went into production with the serial number 1863 and was described as being six feet eight inches long, with four sturdy shaped wooden legs, two pedals, eighty-two keys, and double strung. The completed masterpiece was shipped on October 14, 1858, to Michael Willkomm in Boonville, Missouri, who sold Steinway Pianofortes out of his sale rooms on Morgan Street. He also repaired and tuned pianos.

Now it just happened that Michael Willkomm lived next door to Dr. George W. Stein who had immigrated from Hanover, Germany years earlier. At some point, Dr. Stein became the owner of the piano. In 1862, Dr. Stein married a widow by the name of Balsora Shepherd Furnish*, daughter of Mary “Mollie” Brannin. She brought two daughters to their marriage, Mary and Sarah Furnish.

As roads were forged westward, the lure of the new territory captured the hopes of pioneers. Land was available, and there was talk of gold and fortunes to be made. In March 1864, some of the Brannin family took the trail west. They traveled by wagons and faced rugged roads, storms, Indian unrest, and other perils. My great grandfather was in that number along with a sister, aunts, uncles, a house boy, and cousins among who were Balsora and Dr. Stein, and Sarah Furnish. Mary, sick at the time, followed the next spring with the piano and other furniture. The piano, that had won first prize at the St. Louis Expo, was enough of a prize to Stein that he couldn’t leave it behind. He arranged for the piano to travel with Mary by steamboat up the Missouri River to Ft. Benton, and then by oxcart to its new home in Helena.

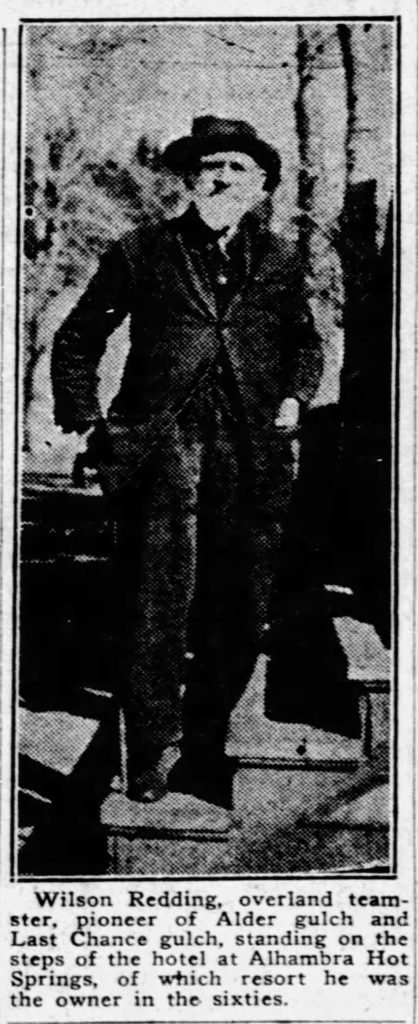

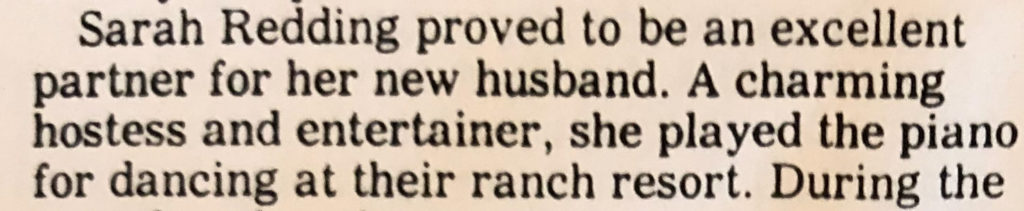

In early May 1866, Sarah Furnish married Wilson Redding who had purchased a hot spring at Alhambra, Montana. Redding, who also had several mining interests, struck gold when he gained his bride. Not only did she bring grace and charm to their home, but she also brought the piano. Just a few weeks after they were wed, weary guests traveling from Virginia City to Helena were welcomed with a sumptuous feast to Wilson Redding’s Hot Spring. As they relaxed from their travels, their spirits were “cheered by the sweet strains of music which the piano gave forth, in obedience to the skillful touch of Mrs. Redding’s practiced fingers.” Through the years, many friends and guests enjoyed the music that flowed from the ivory keys of the Steinway.

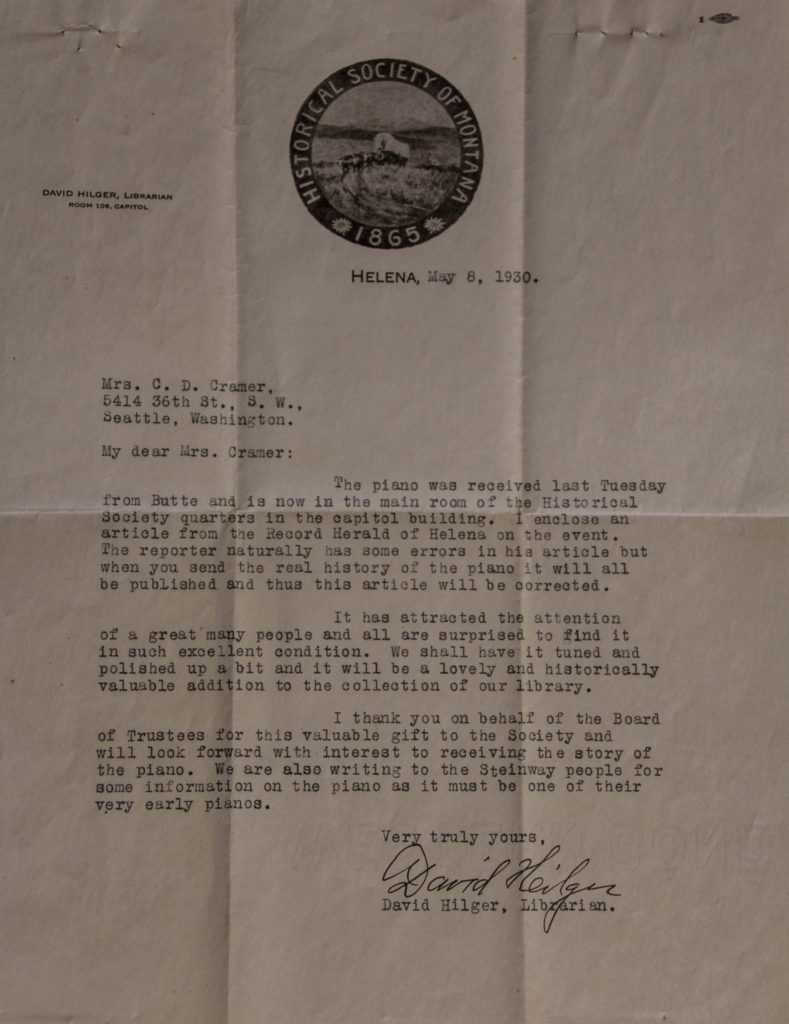

Before Sarah Furnish Redding died, she expressed to her daughter her wish for the piano to be given to the Montana Historical Society. In 1930, her wish was fulfilled. Newspaper articles recorded the event with a brief historical account of how the piano made its way to Montana. The piano fell out of remembrance for a time until a fire stirred in the hearts of some of the family to bring her back into the limelight.

Some of Steinway’s creations are displayed in museums, some given to Presidents, others purchased or played by famous musicians before millions of awed audiences. And then, there is one lone disassembled square piano with serial number 1863 leaning against the wall in the basement of the Montana Historical Society Museum waiting for someone to clean off the dust, tune her strings, and put her on display. Even if she can’t be tuned, she is still a gorgeous instrument and deserves to have her story told and placed in the annals of history. It is a dream to have her grace the halls of history, her keys gently played to unlock her mellow tones and release her song that has been silent for far too long – a song that reminds us that silence is not always golden.

1926

- note: The first husband of Balsora was Barnett Furnish, a man of some means. He died on a return trip from California in 1854 in Platte County, Missouri after he and others drove cattle to the California market.

WOW !