Daddy had been told to not be surprised if Uncle Rube didn’t know him. The old gentleman had suffered a stroke that affected his memory. As we walked into the room at the Pioneer Home, Uncle Rube looked up. He took one look at Daddy, stood to his feet, raised his hand, pointed his finger and said, “Th-th-that d-d-danged sp-sp-spotted horse!” Spot, the spotted horse, had stepped on his foot thirty years earlier and left Rube’s big toenail hanging by a sliver. More than once, Daddy and Rube had shared that memory.

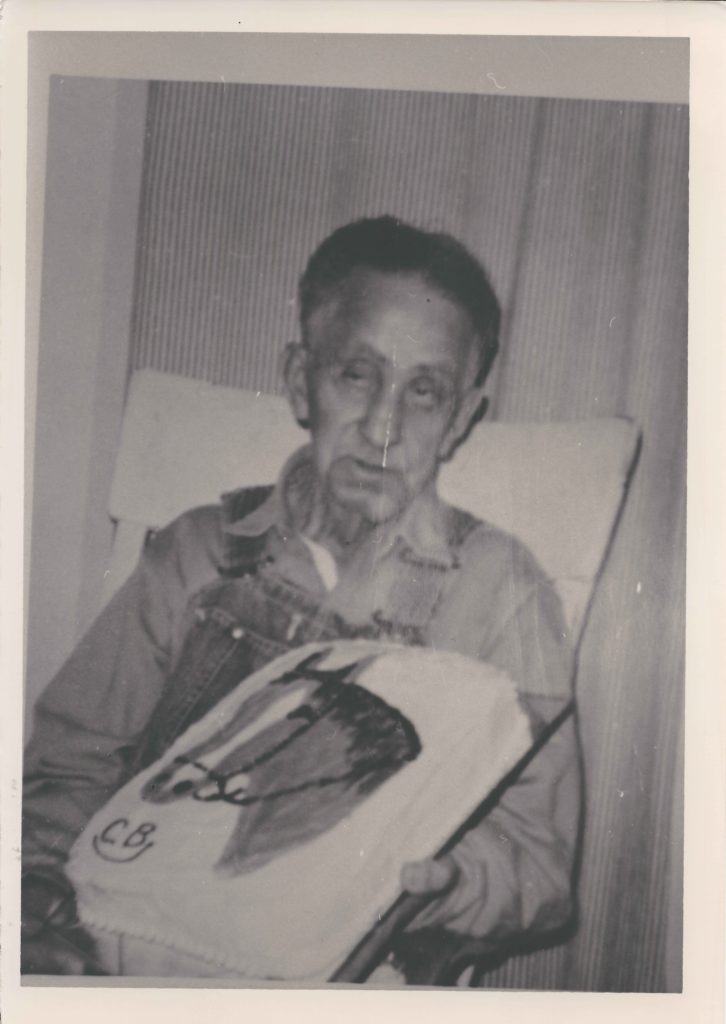

Rube in Pioneer Home

Even without the stroke, Uncle Rube was considered slow or “retarded”. His drawn, drooping face looked much like I had remembered. Though Uncle Rube lived in a man-sized body, he was just a boy. Just one look at him turned back the hands of time to 1895 when he was a boy of five years old.

Four covered wagons drawn by four-horse teams, and a spring wagon pulled by a team of mules topped Apache Hill. Guadalupe turned around for one last glimpse, but the ranch along Sapillo Creek had already disappeared from view. Eight children were born to the family in the little log cabin in the valley they left behind. Guadalupe carried those memories and many more with her as the wagons turned toward Montana Territory that morning of May 30, 1895.

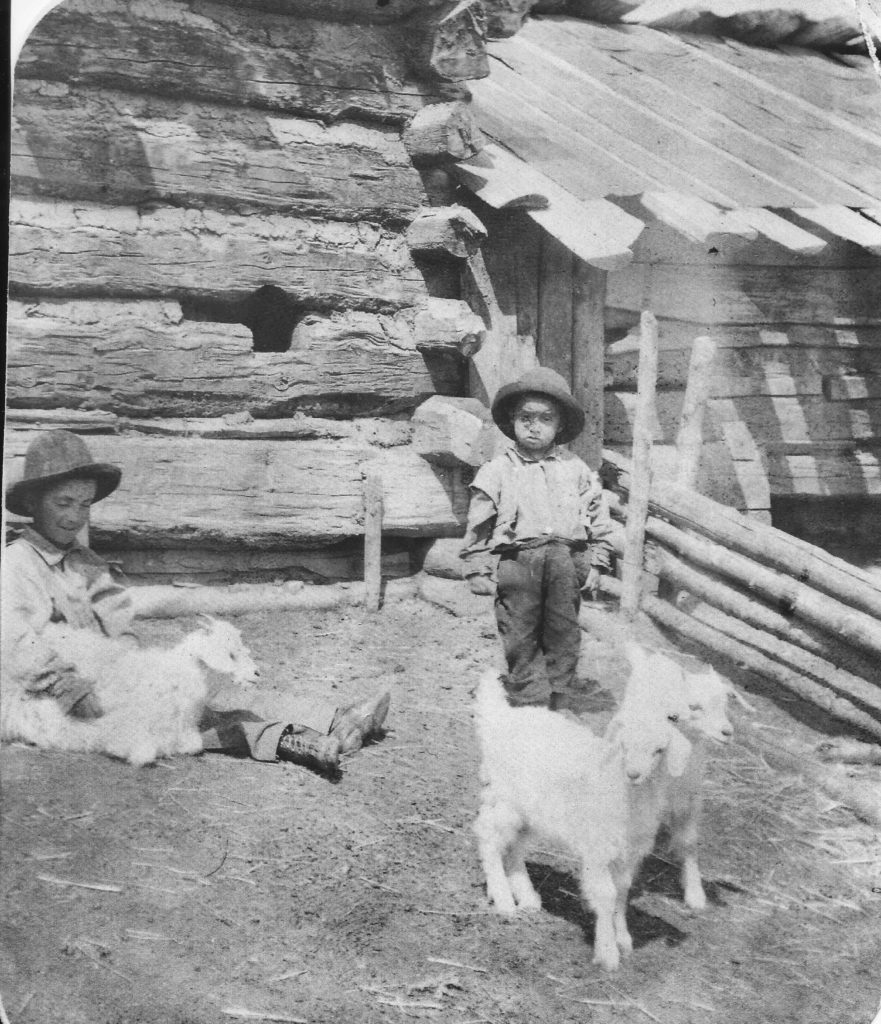

The older boys had gone on ahead with the herd of goats, burros and horses. Guadalupe, her husband, their eleven children, the youngest six months old, a son-in-law, and one-month old granddaughter, were joined by other friends who traveled with them. Little Rube rode in the wagons with the other small children.

The route from New Mexico Territory led them into Arizona and northward through Utah. A year before, Guadalupe had a dream of a long hard trip. As they approached Woodruff, Arizona, Guadalupe described that very town just as she had seen it in her dream, though she had never been there.

It was dry and hot. Water was scarce. Drinking from the Little Colorado River, the boys tried the strain water through their teeth. They ran their finger around their gums to remove the silt. Even when they tried to filter the water through a flour sack, it did little good.

Near Flagstaff, most of the family came down with typhoid fever after drinking contaminated well water. The oldest daughter became deathly sick. Her milk dried up and she was not able to nurse her baby. Guadalupe not only tended to the sick and nursed her own little girl, but she also shared her supply of breast milk with her granddaughter.

Little Rube had the most severe case of typhoid fever and developed double pneumonia. Rube’s father had a doctor from Flagstaff come to see the little boy. His high fevers caused brain damage, affected his speech, and left him handicapped with partial paralysis, his legs becoming so weak, his sister two years his senior had to teach him to walk again. Rube did survive. His family nurtured him, and his brothers gave him some good-natured ribbing. He never went to school or learned to read and write, but he did many of the chores, rescued his chickens from the cook, and knew how to smoke a pipe.

Uncle Rube lived to the ripe age of eight-one. To some, he was a giant among men but on the inside, he was a five-year-old little boy who wore overalls.

Rube & brother Sid