The young boy turned the page. He gave rapt attention to each word. The exploits of Buffalo Bill and other Western legends seemed to leap right off the pages from the dime novels he read. “One day,” he thought, “I will go west.” The lure of the Western Cowboy culture drew him from the city streets of Washington, DC, where he had grown up. Maybe one day he would be famous.

Harvey Whitton was an intelligent young man, having been educated in the schools of the nation’s capital. He was of mixed race, described as being hot tempered, 5’10”, had a flat nose, dark eyes, thick lips, round face, heavy jaws, a frowning expression and walked slightly bow-legged. In 1893, seventeen-year-old Whitton embarked on his journey, finding work in St. Joseph, Missouri and Greenleaf, Kansas, before arriving in Bozeman Montana in 1894. The summer of 1895, he became acquainted with Frank Morgan, an alias of Frank Straiter (or variant spelling). In the fall of 1896, the two went to work for a ranch outside of Bozeman. After a petty quarrel, Morgan pistol whipped the rancher. A warrant was issued for his arrest. Afraid he would be charged with something worse, he escaped to Madison County. When Whitton got word that Sheriff Fransham and his deputy, Jack Allen knew of their whereabouts, he warned Morgan. Here is the account as noted in the Gallatin History Museum:

“For a number of months, two young toughs had terrorized the Belgrade and Manhattan areas with vicious beatings, saloon robberies, and roadside holdups. Sheriff Fransham learned that the two men might be hiding at Carpenter’s Ranch, twenty-five miles west of Bozeman. When they arrived at the horse ranch, gunfire ensued; Deputy Allen’s gun misfired and, unprotected, he was shot in the head. After further exchanges of gunfire with the sheriff, the gunmen rode off. Dr. Chambliss rode out from Bozeman to attend Allen, bringing him back by horse-drawn ambulance. After many days of agonizing pain and convulsions, Jack Allen died on February 2, 1897.”

Whitton, under the alias of James Hall, made his way to Elko, Nevada where he was apprehended and returned to Montana to serve a sentence of 89 years for the murder of Deputy Sheriff Allen of Bozeman, Montana. While in Montana State Prison at Deer Lodge, he was not idle. He was the mastermind behind heinous schemes he directed from his prison cell. He was instrumental in the orchestration of the Dodson murder, and took part in the Gravelle dynamiting outrages that was part of an extortion attempt to line their pockets with $50,000 from the Northern Pacific Railroad. Whitton claimed that Gravelle had created the plot in 1903 while his cellmate though Whitton himself was actually one of the composers of the extortion letters.

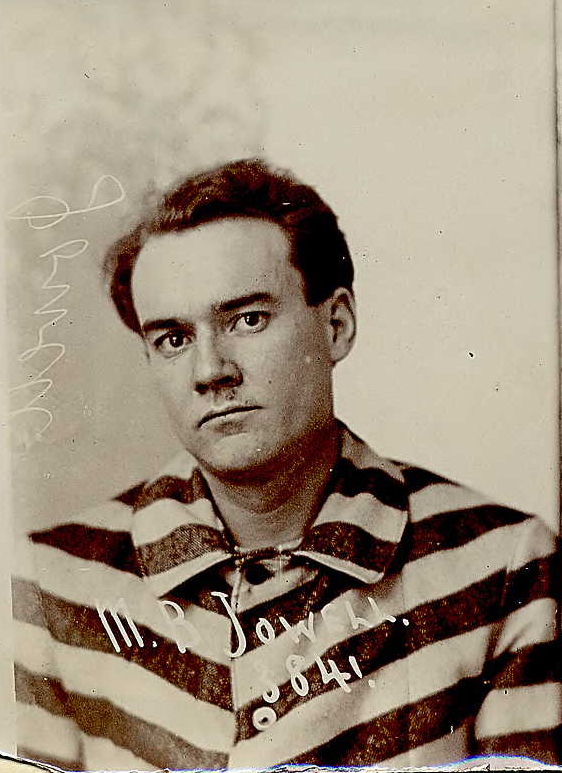

In 1906, Mel Jowell was sentenced to Montana State Prison. He was a horse thief, cattle rustler, altered brands, and was believed to have murdered a sheriff in Arizona. Paroled in the spring of 1909, he was back in prison by fall. His discharge for that stint came in May of 1911. While in prison, Whitton and Jowell formed a dangerous alliance. Upon Jowell’s release, he stole the life of young Deputy Sheriff Joseph Brannin, his life snuffed out at the age of twenty-eight. Jowell escaped to Phoenix, Arizona under the name of Dalton Sparks, and was arrested on Christmas Eve and returned to Deer Lodge to finish out his prison term.

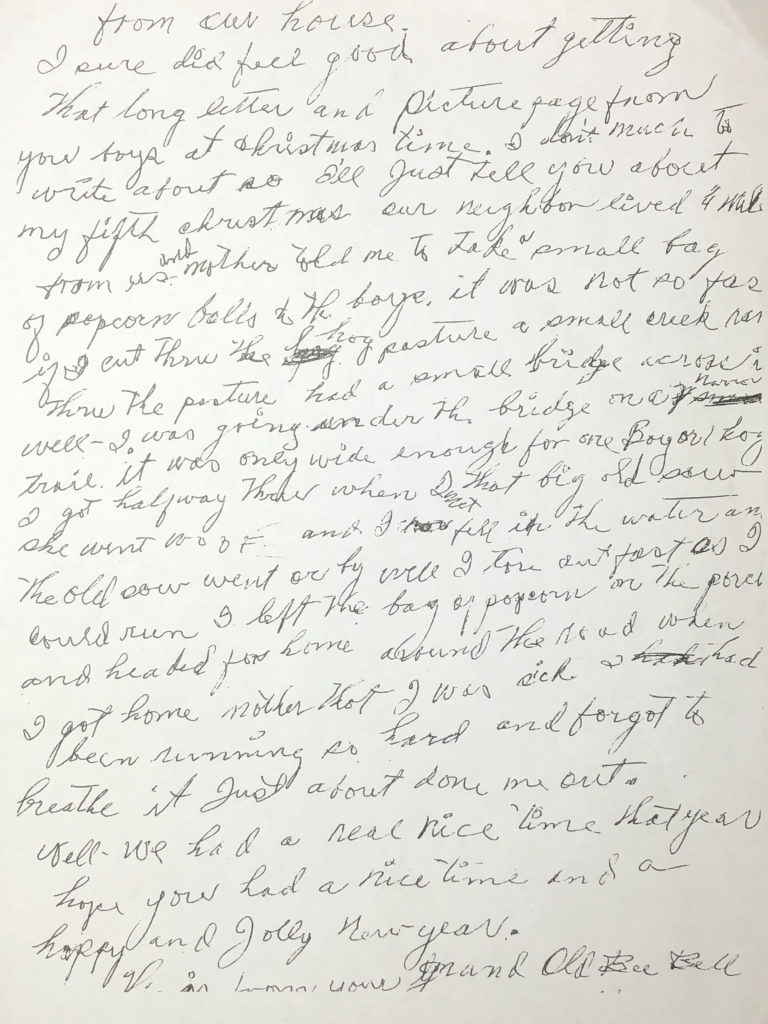

In the meantime, in 1910, a letter was penned to beg the release of Harvey Whitton. The letter was written and sent on behalf of Dolly, a blind sister of Whitton, who was living at the Young Woman’s Christian Home on C street in Washington, DC. Dolly had only learned of her brother’s whereabouts on her mother’s deathbed when Nellie Whitton revealed to her daughters the events concerning their brother Harvey. Mrs. Whitton was informed about her son after reading an article in the paper in January of 1897 and began the inquiry of her son’s well-being by correspondence with W. C. Latta in Bozeman, Montana. Dolly called upon Grace Thomas, a young business woman, who penned her appeal for the release of her brother. The letter pricked the heart of Montana’s Governor Norris who was in Washington DC for a Governor’s conference. He promised to speak on her behalf. Dotty believed her beloved brother would be released, magically transformed and come to her aid to care for her in her time of need. The Governor’s attempt failed for Whitton’s premature release. However, not long after, he was released for “good behavior.” There was little or no regard given to the fact that during those years he directed brutal crimes from his prison cell.

Whitton’s release came September 9, 1911, just two months before his former prison mate, Mel Jowell, shot down Joseph Brannin on the streets of Melville, Montana. It is recorded that Whitton went to Butte and lived an “honest life”, at least until the summer of 1912 when once again, he found himself on the wrong side of the law. He did not travel to Washington DC to care for his sister, though the authorities had promised to fund his mission until he could find employment. I would say those ten months were a short-lived “honest life.”

The summer of 1912, Mel Jowell along with another prisoner, John McAdams, were transported to Livingston to testify in the trial of George Ricketts, another prison mate of Jowell’s and Whitton’s charged as a co-defendant in the murder of Deputy Sheriff Joseph Brannin. On the return trip to Montana State Prison aboard the Northern Pacific #41 train, the two, chained together, escaped from a bathroom window on the moving train as it slowed along Pipestone Pass. After the two were separated from their shared bonds, Jowell headed south. Somewhere along the way, he was aided and abetted by one Jim Ross. The two made their way to Elko, Nevada. A series of events led to their arrest. Jowell was arrested under the alias of Rex Roberts. His partner Jim Ross was none other the Harvey Whitton. Whitton had returned to the same place he was captured in 1897 after the murder of Deputy Sheriff Allen. Seems a bit ironic, doesn’t it?

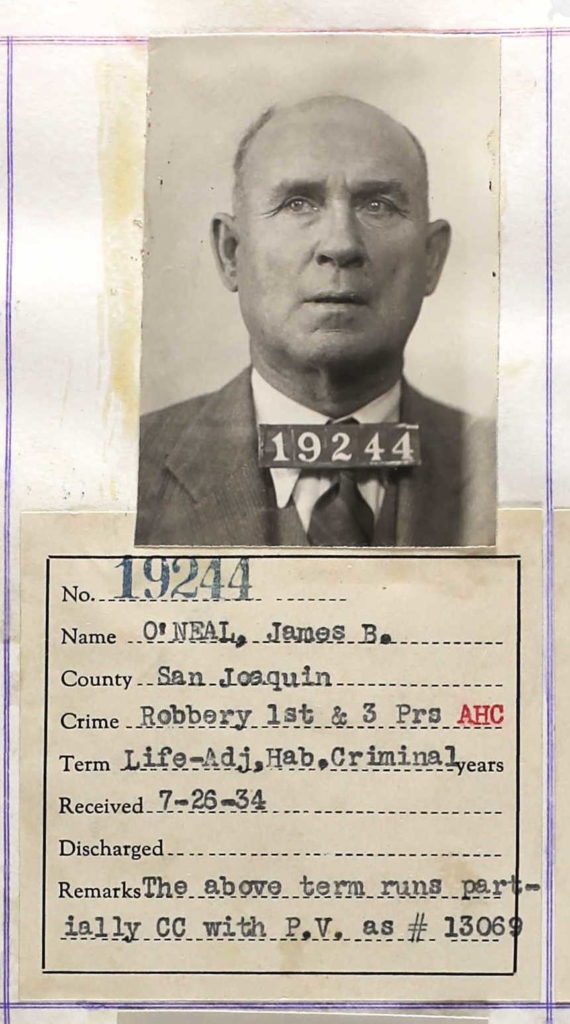

The two were sent back to Deer Lodge, Montana State Prison. Jowell, also gifted with words, charmed his listeners and readers and influenced the authorities by his letters of appeal, and eventually bought his freedom with words and “good behavior.” Whitton continued his life of crime under yet another alias, James B. O’Neal.

The mother of Harvey Whitton never saw her son again, nor did his sister, Dolly, rest in the arms of her beloved brother she so longed to see. Whitton did find fame – not the kind that would make a mother proud, and not the fame of the renown heroes of the West he read about as a boy. He traveled the hidden trails of notoriety with outlaws who left behind women and orphans to grieve in the wake of gunsmoke… and to think it began with a cheap dime novel…

Mal (Mel, Mallie) Jowell (Jewel, Jouel, Joel), alias Dalton I. Sparks, alias Rex Roberts

Harvey Whitton (Whitten), alias James Hall, alias Jim Ross, alias James B. O’Neal