Though the noise of battle moved away, the soldier, not much bigger than a boy, still heard the barrage of gunfire echo in his mind. Every little sound brought him to attention even though burning pain exploded through his body. The smell of war hung heavy in the thick smoke-filled air, his nostrils aflame from the distinctive sharp lingering odor of acetone from the cordite explosions. The haunting image was burned in his memory and would rear its ugly head and cause flashbacks for over seventy years.

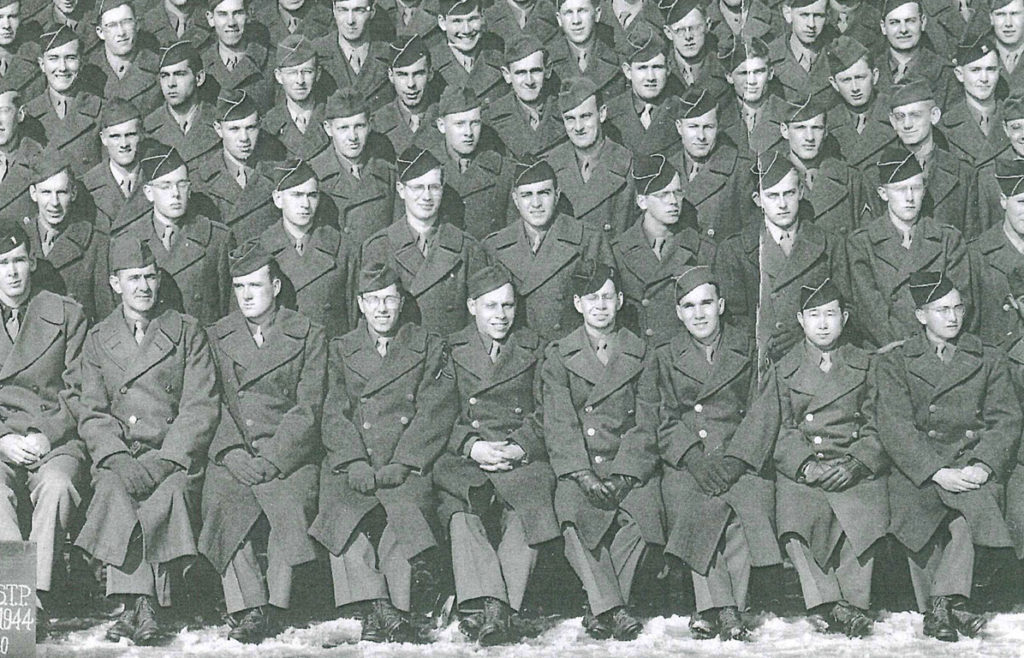

the “little soldier”, right on first row; fellow soldier Halash, far left on second row is in another story

He, along with other wounded ambulatory soldiers, moved slowly through the battlefield bathed in blood. Some of the injured were carried off the field, some to be transported to hospitals, some to receive their last rites. Those walking joined the ranks of soldiers needing medical attention as they packed into jeeps to be taken to the field hospitals. That was December 2, 1944, the Battle for Flossendorf.

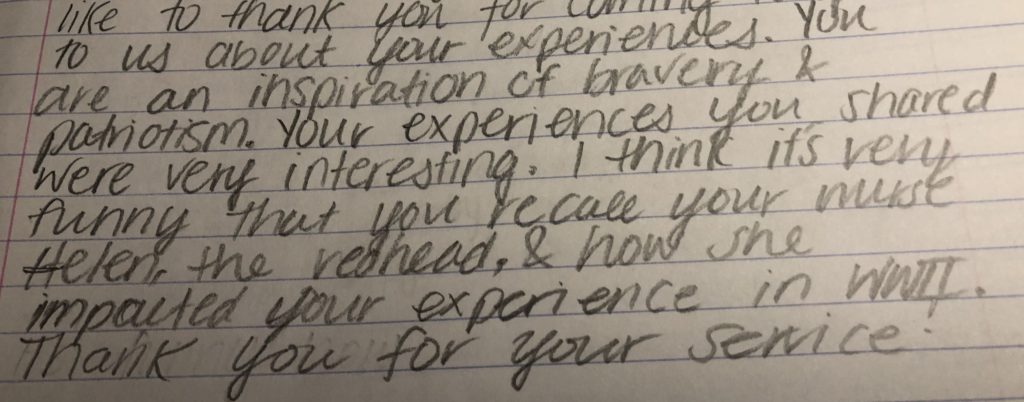

When the soldier awoke, he was in a tent and still caked in mud. A nurse cut his clothes off, replacing them with a standard issue gown that exposed the backside. A couple of days later he was evacuated to a hospital in England. The hospital ward was a long Quonset hut staffed with two doctors and nurses by day and two of each by night. One of the nurses, Catherine, was kind and sweet. The wounded men all loved Catherine. The other was a redheaded nurse, Helen. She was “a heller.” She “gave them hell” and they didn’t like her. She had been jilted by her doctor boyfriend and she “took it out on anybody wearing trousers or long handled underwear under their raincoats.”

It didn’t seem like there would be much celebrating that Christmas. Soldiers were separated from their families back home and doctors and nurses were pushed to the max to tend their wounds. Some men didn’t make it. Some carried the scars of war to a ripe old age.

Amid the stench of death and amputated limbs, one doctor assigned to them offered a taste of celebration. He gave each a shot of whiskey and wished them a Merry Christmas. Little did the wounded GIs know they were to be recipients of a greater Christmas gift.

The soldier made his way to the latrine, walking down the aisle that separated two rows of bunks. His walk was not straight like a man marching in cadence with his unit. He shuffled his feet to the cadence of the rise and fall of moans and groans, some of those his own as he gave way to the wound where the shrapnel hit and lodged in his rib.

That caught the attention of Nurse Helen. “Soldier, when you walk here, stand up straight and walk like a man!” The soldier jerked to attention, gritted his teeth, and walked straight. He didn’t like her any better!

A few days later, about Christmas Eve, a bedridden soldier, “Tex”, had a flare up. He had a seizure, gasped and turned stiff. They just knew he was dead. Nurse Helen came running and jumped into action. She pounded on his chest, did something with tubes and needles, and pulled Tex through. She saved his life.

That redheaded nurse became a hero in the eyes of the wounded men. To show their newfound respect, they all walked straighter and taller.

Though I don’t know who Nurse Helen was or what happened to her, I thank her for giving my father a special gift the Christmas of ’44. Years later, the little soldier told his stories to students over a period of several years. Students sent letters of thanks, many touched by his story of the redheaded Nurse Helen. And so his story continues…..