People came for miles to bring their watches and clocks to be repaired by the watchmaker of Holbeach. They were amazed to watch his hands at work. Fingers of the artisan placed each delicate piece in place, connecting every minute spring and pressing each tiny gear in the proper position. Each unique work of art responded to the master’s touch as the hands on the face kept time, ticking past each number.

this old family clock could use a touch from one of the Rippin clockmakers

William Rippin was no ordinary watchmaker or repairer of clocks. He did not use the aid of magnifying glasses that craftsmen of the trade needed to see the intricate workings of the inside of the watch or clock. He did not use vision at all. You see, Mr. Rippin was blind. While others relied on their sight, William relied on touch. Around the age of twenty-five, William caught a severe cold in his eyes. Various treatments were unsuccessful. The result was amaurosis. At the age of twenty-eight, William was hopelessly blind.

Instead of being defeated, he became a master horologist. What some saw as misfortune was turned into perseverance and skill. His ability to repair clocks, watches, musical instruments and every tiniest of item connected with the business was remarkable. The only aid required was the assistance of his wife in the unpinning and pinning of the hair-spring. He trained her to work at the business after the loss of his sight. There could be a hundred watches in the shop for repairs at one time. He knew every watch by touch.

As has been the pattern throughout the years, some people will try to take advantage of those deemed as handicapped. William seemed an easy target. Once he was robbed, the stolen pieces consisting of “watch-wheels, hair-springs, and other tiny things belonging to the trade.” When the thief was apprehended, the stolen items were identified by Mr. Rippin by a mere touch of his hand.

His daughter described him in a letter to the editor of The Standard, October 14, 1887, as “an intelligent, handsome man, standing five feet ten inches high, and many who saw and conversed with him were unaware that he was blind.” After his death, his wife and daughter carried on the business at Holbeach.

There is a stained glass window in All Saints Church, Holbeach dedicated to “William Rippin, the Blind Watchmaker and his wife Ann”. It depicts the gospel story of blind Bartimaeus when he received sight. The memorial was placed there by Mr. Rippin’s daughter.

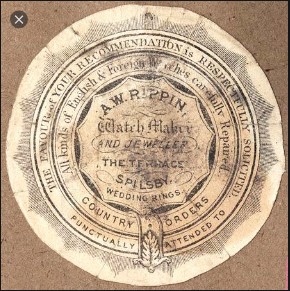

William Rippin, along with his brother Joseph and James, learned the trade of watchmaking from their father, James Hall Rippin. Census records and parish baptismal records of James’ numerous children verify his occupation. Others followed in his footsteps. “The Rippin family of clockmakers from the South Lincolnshire towns of Spalding and Holbeach are recorded from around the middle years of the 18th century for most of the following two hundred years.” Alfred William Rippin, a son of James, brother of William and Joseph, continued the trade and relocated to Spilsby. His seal has been on display at the British Museum.

This is not just some fascinating tale. In a world where people are ridiculed for their handicap or for being different, it is a tribute to those who are artisans despite the barriers.

“The unique skeleton clocks with their frames based on the ellipse are invariably signed, simply, ‘Rippin Spalding’. Despite the proliferation of Rippin clockmakers research favours James (1820-1884) as the most likely maker of these clocks.“

William Rippin is my husband’s 2nd Great Uncle.

Joseph Rippin is his Great Great Grandfather.