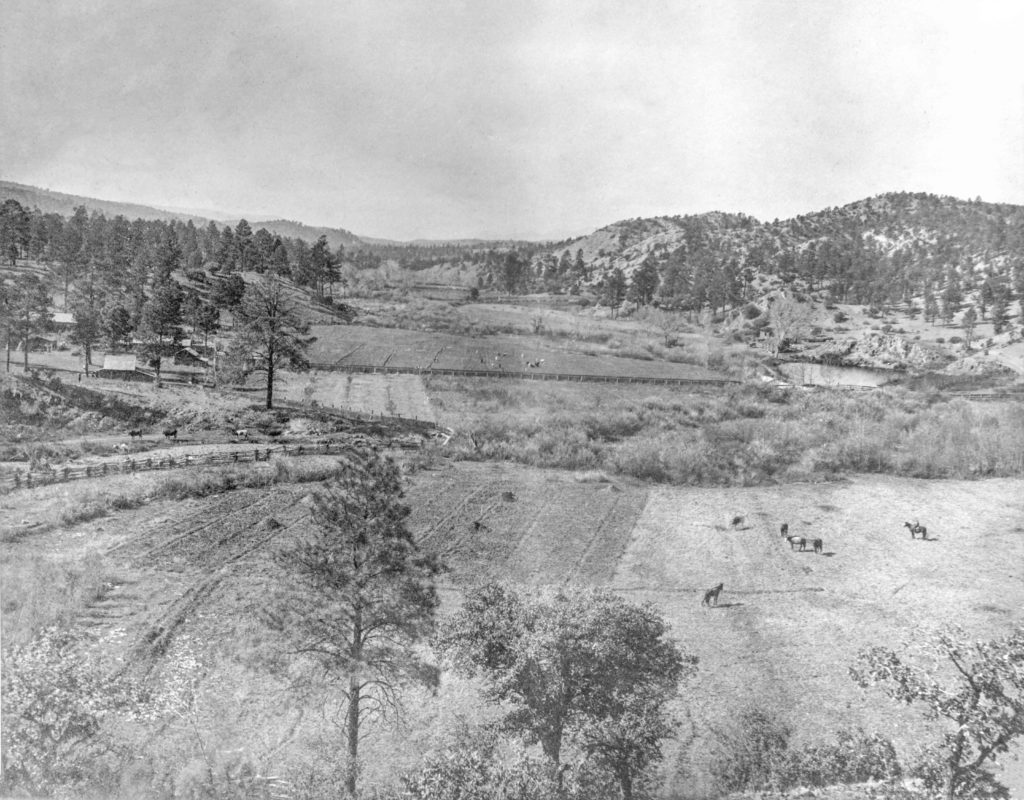

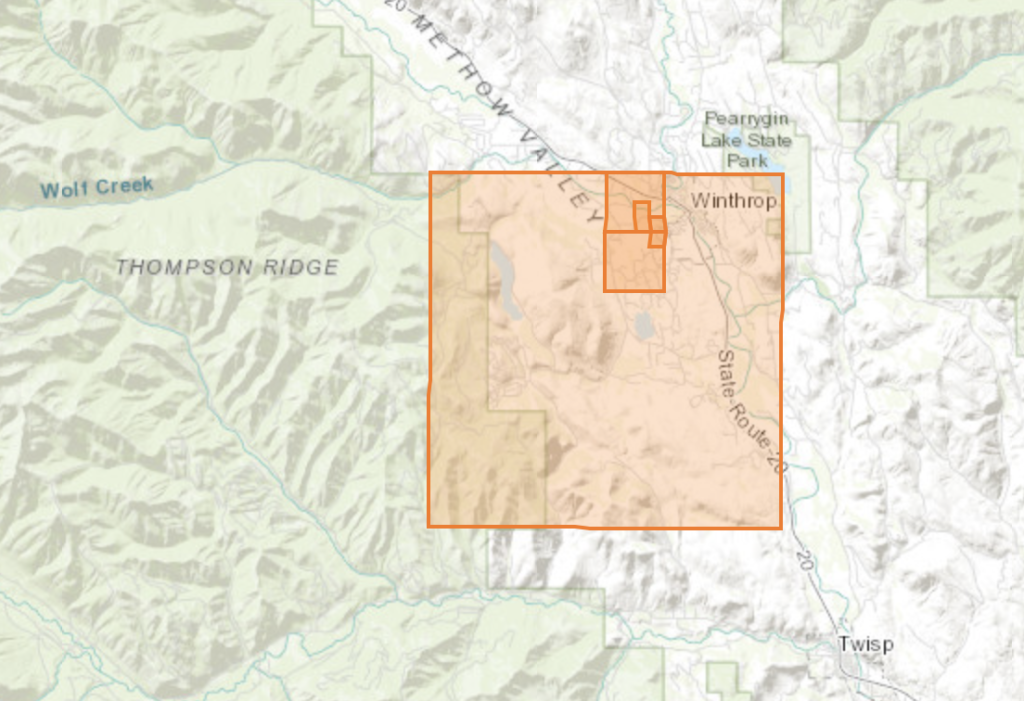

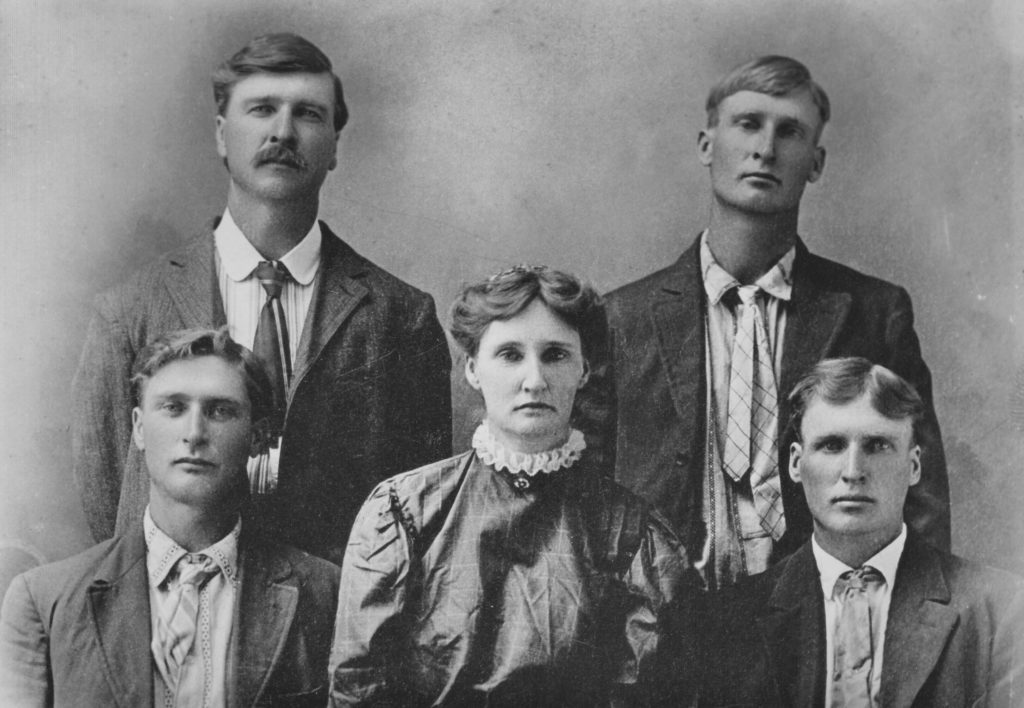

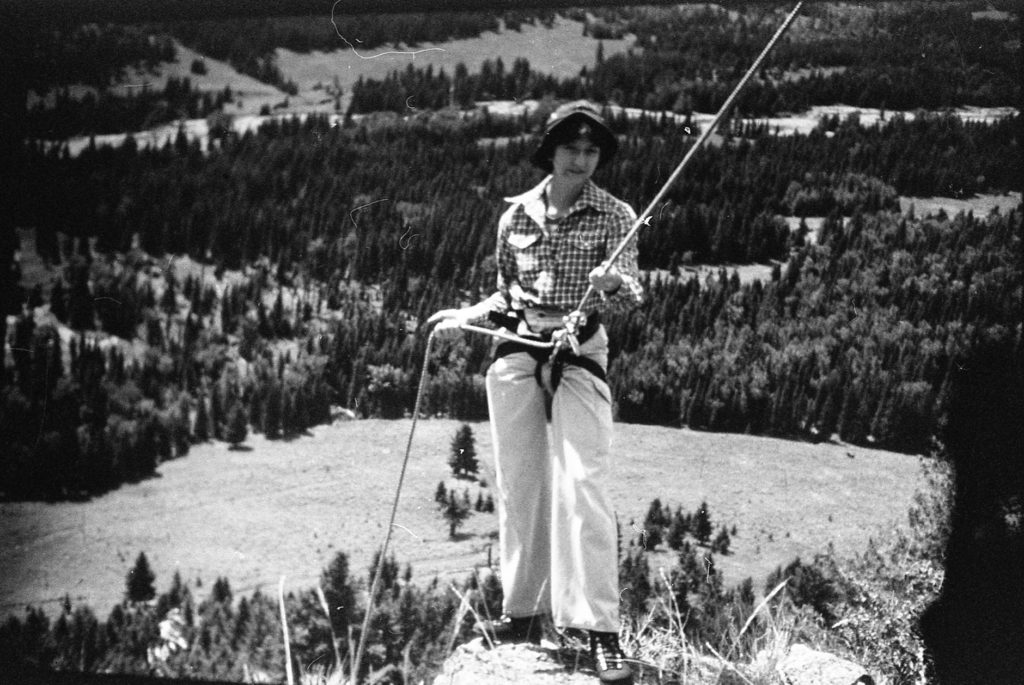

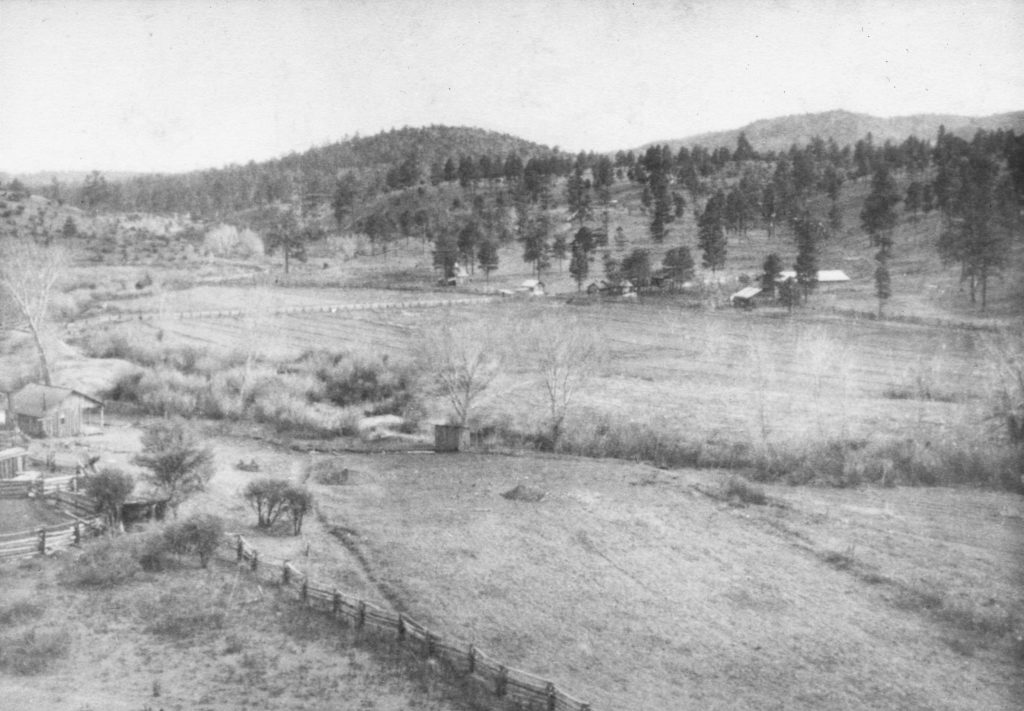

The Apache Scout looked down on the Brannin Ranch where Sapillo Creek wandered through the valley. From that vantage point, the scout had a clear view of one of the Brannin boys on horseback who watched the stock grazing. Across the field, Guadalupe and some of the kids were busy with household chores and other projects. Smaller children played in the yard around the log cabin. The corral, barn and other buildings were in clear view. That wasn’t the first time Apache scouts made their way to the Brannin Ranch. They visited from time to time, often unseen. For the most part, except for an occasional cow taken for their livelihood, the family and stock were left alone, maybe because the Brannins allowed them food on occasion, maybe because Guadalupe could have passed as one of their kin, or because they believed she might just be the daughter of their revered Chief Victorio.

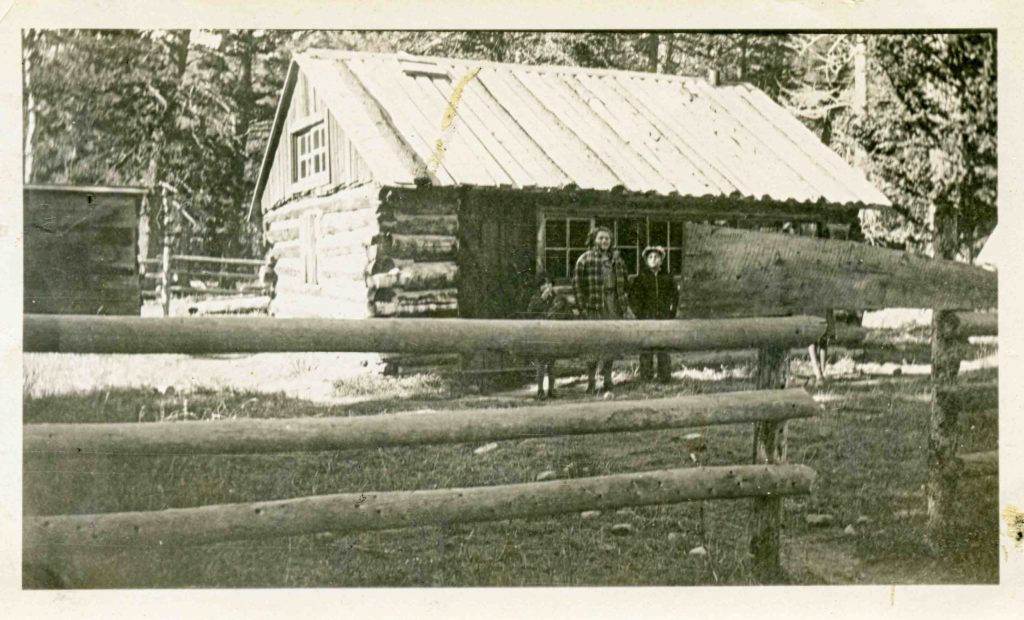

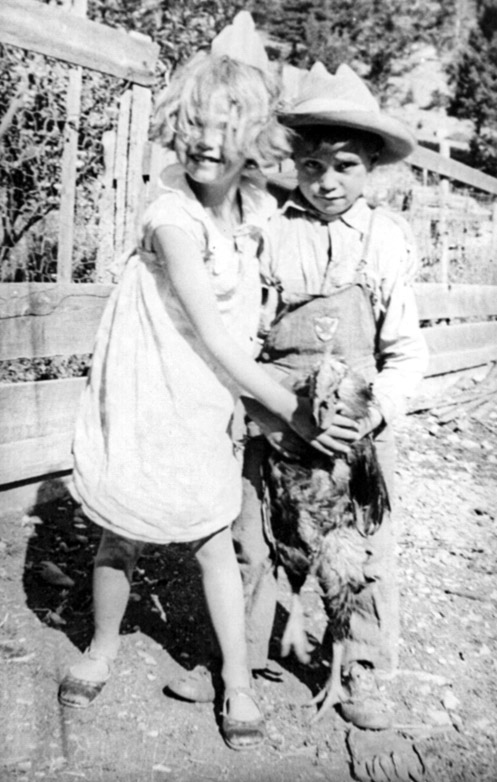

The ranch along Sapillo Creek was thirty miles from Silver City, New Mexico. In 1876, Stanton Brannin left the mining town of Georgetown and set up a sawmill on the property on the Sapillo. A log house, corral and barn were constructed. Later, a shingle machine was added. Stanton also planted an orchard of apple trees. Eleven kids grew up in sight of those trees. If only trees could talk, they would have informed the family of more than just the presence of Indians and strong-armed land hungry ranchers who passed through the property.

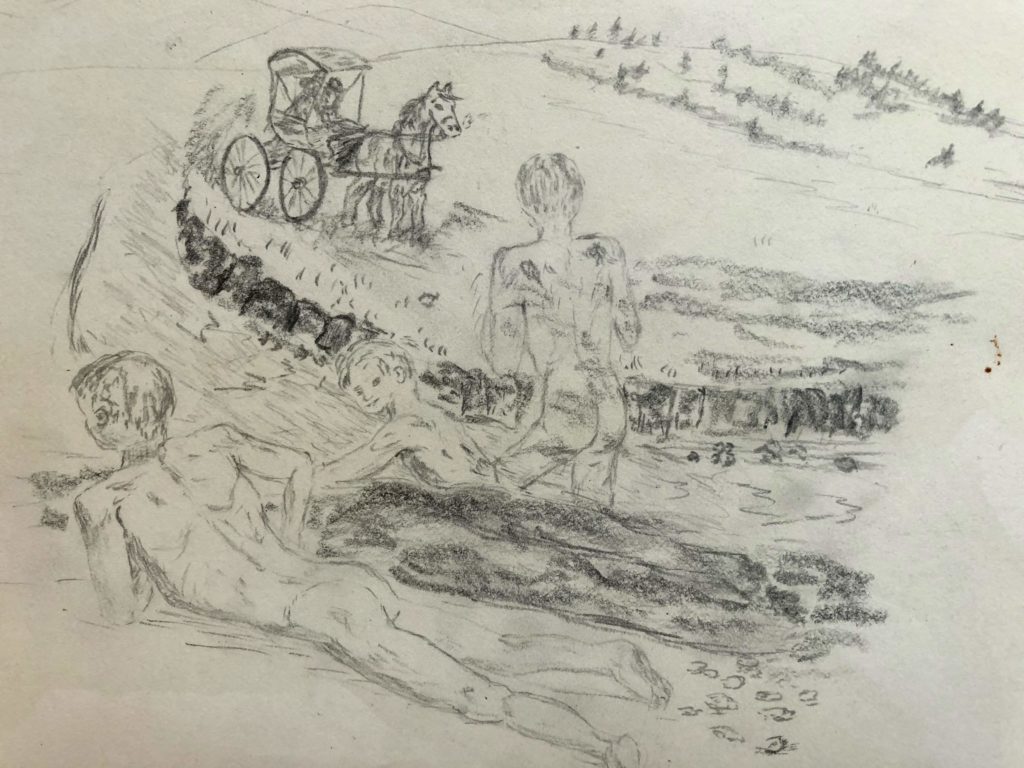

The boys were always looking for adventures and didn’t have to go far to find them. On a lazy Sunday afternoon, they offered great entertainment at the astonishment of neighbors out for a Sunday drive in their wagons. There was a great repository of mud by the creek. The boys stripped down to their birthday suits and rolled in the mud until they were amply covered. When an unsuspecting couple came by in their wagon, the boys jumped out and danced like madmen. The horses spooked and gave their passengers quite a ride. It didn’t take long for the boys’ father to catch wind of their performance. That put an end to that!

Along with cattle, horses, and Angora goats, they also had some burros. The boys hated the burros, especially Dick. He would much rather ride a horse. It was an insult to have to ride a burro. The burros were slow, lazy, and stubborn. The boys decided to drown one of the nasty beasts. They tied a log to its halter and pushed it into the swollen creek in the swimming hole. The ploy did not work. Little did they know the log would float. It drifted to the edge of the creek and the burro just walked out!

Maybe the trees would have told about the Apaches who camped at the pond near the Brannin cabin. The Indians may have grabbed an apple or two on their way to borrow and return a pair of scissors to cut their hair. Maybe the trees saw the ghost of Charley Woods walk through the orchard before he climbed up the pole in the barn. Maybe they heard the boys beneath their limbs as they conspired to string barbed wire at neck height from one side of the draw to the other with the intent to slit the throats of GS cowboys.

That’s when Stanton decided it was time to move the family. He left the untamed wilds of New Mexico in 1895 to more civilized lands – the untamed wilds of Montana. In 1896, they had made it to their destination where their last two children were born.

One hundred years later, descendants of Stanton and Guadalupe Brannin gathered at the site of the Brannin Ranch on the Sapillo. Still standing, twisted and weathered, were a few apple trees. Sixteen years after that meeting, we stood in the same place again and had our picture made with the last lone tree planted by Grandfather Brannin about one hundred thirty-four years earlier.

If only trees could talk!