Two men tumbled out the door of the saloon. Shots rang out in the streets of Melville, Montana. Deputy Joseph Brannin fell dead to the ground. Mel Jowell was on the run. The Sheriff formed a posse and was soon on the trail of the outlaw. Less than a year later, another posse chased Jowell after he escaped on the return trip to prison after testifying at the trial of his accomplice. A trail of crime followed Jowell to Elko, Nevada.

We grew up hearing true life stories just like you’d see on the old TV Westerns. In fact, the last time Jowell was seen by any of our family was on a Western movie set in California. Cousin Clancy, nephew of Joseph Brannin, was a Western movie actor. When the “extras” rode onto the set on horseback, Clancy spotted Jowell. He asked, “Where’d you learn to ride?” Jowell responded, “Melville, Montana.” They recognized each other but Jowell didn’t stick around to spin yarns about Melville days. Through the years that followed, rumors were heard but no definite answer was given as to what had transpired in the life of Jowell. We took up the chase and uncovered interesting stories and documents. After years of prison and life on the run, Jowell returned to his home state of Texas, married, had a family and lived to a ripe old age.

Just like another posse in pursuit of Jowell, the trail led us to Elko over 100 years later. Passing the city limit sign brought excitement as we anticipated uncovering part of the mystery that shrouded the outlaw. After a bite of breakfast at the Coffee Mug, we walked to the Elko County Court House.

Our search was for legal documents that hopefully would give details concerning Jowell. The clerk was amazed hearing our brief account of the events we knew. We told about the day Joseph Brannin was killed, of Jowell’s escape and capture in Arizona, of the trial and sentencing to 22 years, of the trial of Ricketts where Jowell testified, and of the return trip to Deer Lodge on the Northern Pacific #41 Train. The lady’s eyes got big when we told of Jowell’s escape from the toilet window of a moving train near Pipestone Springs while handcuffed to another prisoner just prior to his appearance in Elko. We explained that it was obvious the escape was orchestrated. Records indicated that Harvey Whitton was one of his “friends” who aided his escape after Jowell jumped from the train. That name soon took on an even greater significance in the story.

The clerk presented a ledger that contained records for 1912, but the name of Mel Jowell was not listed under any of the various spellings of his name nor his alias, Dalton I Sparks. So, where was he? How could there be such a discrepancy from the articles we had uncovered?

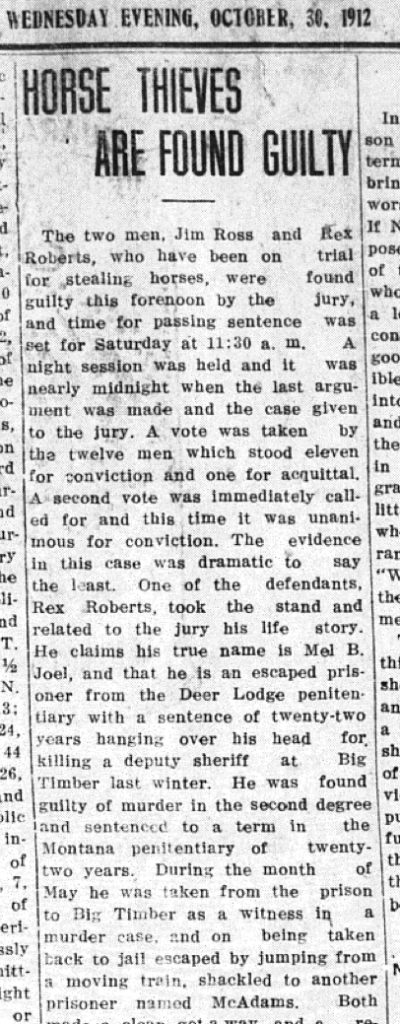

Feeling a bit dejected, we made our way to the library. There had to be something we were missing. We began searching through newspaper articles for 1912. Bingo! That’s why we didn’t find him! He had another alias of Rex Roberts. Armed with new artillery, we went back to the courthouse. Out came the ledger again, and there he was – Rex Roberts and his cohort Jim Ross. Come to find out, Jim Ross was also known as James B O’Neal and Harvey Whitton, a hardened criminal who had been with Jowell in Montana State Prison in Deer Lodge.

The clerk asked if we knew how to run a microfilm reader. Yep! She gave us the reels and free rein to use the reader that also had the ability to save documents as PDF files. Out came a trusty Flash Drive! We were able to access the complete court case and other documents attached to that file. We hit pay dirt!

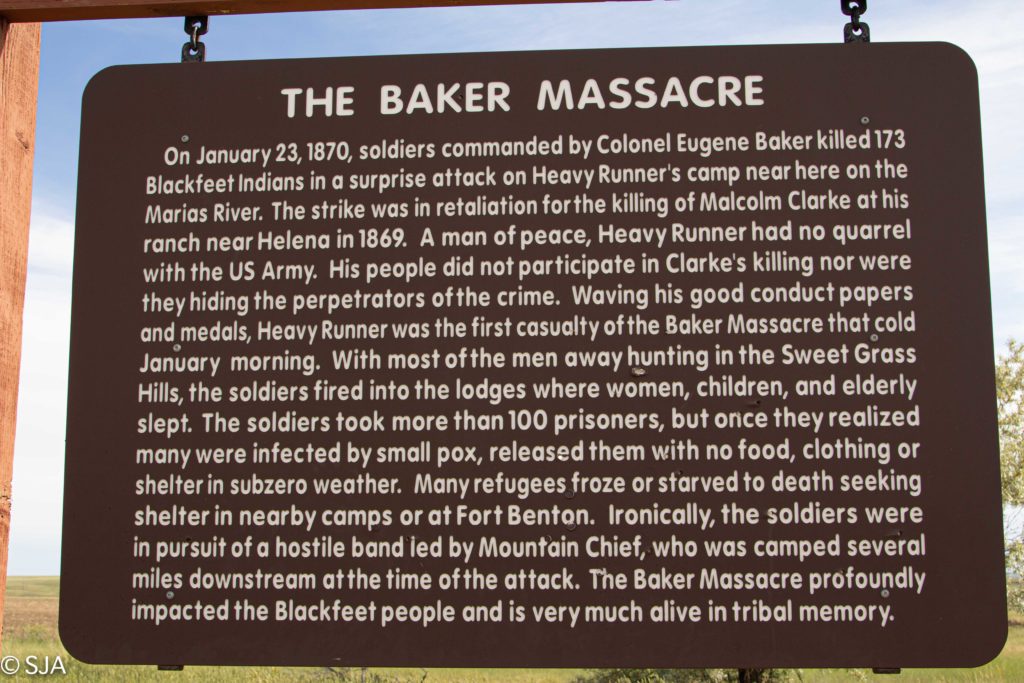

A few days later we were on Pipestone Pass near the area where Jowell had escaped from the train. We followed back trails over the mountain into the rough and rocky wilderness expecting to see outlaws peering from behind the rocks. A few days after that we were at Sweet Grass County Courthouse photographing court documents of the trial of Mel Jowell. Driving through the little town of Melville, I could almost see Jowell and Uncle Joe tumble out the door of the saloon and hear a shot ring out. And so began the chase of an outlaw.

In brief, Jowell and Ross were arrested for horse stealing. Jowell served time in Nevada before being returned to Montana State Prison where he served only part of his sentence before he was pardoned by the Governor of Montana.